ReutersA farmer sampled some sunflower crops lost to the heat in Ergelija, an Albanian village, in late August. Hundreds of wildfires have raged in the western Balkans recently.

ReutersA farmer sampled some sunflower crops lost to the heat in Ergelija, an Albanian village, in late August. Hundreds of wildfires have raged in the western Balkans recently.

1:30 p.m. | Updated

A small bit of good news about food prices from the Food and Agriculture Organization, a United Nations agency in Rome: The price spiral seen earlier this summer as markets reacted to droughts and other bad news has leveled off, with the agency’s closely watched index of global food prices essentially unchanged in August compared with July.

Prices are still up sharply from earlier in the year and remain high by historical standards, the F.A.O. said Thursday, but they have not reached the peaks seen in 2008 and 2011. The agency held out hope that a third global food crisis in five years might yet be averted.

Perhaps the biggest single question about climate change is whether people will have enough to eat in coming decades.

We have had two huge spikes in global food prices in five years that were driven largely by chaotic weather. And this year we may be in the early stages of a third big jump. Droughts and heat waves have damaged crops in many producing countries this year, including the United States and India.

As my colleague Annie Lowrey reported this week, United Nations agencies are hitting the alarm button.

Now come two reports that help to frame the problem of the future food supply — one of them offering a stark warning about what could be in store, the other offering a possible way out.

As readers of an article I wrote last year may recall, growing scientific evidence suggests that climate change is already functioning as a drag on global food production.

Rising temperatures during the growing season in many large producing countries are cutting yields below their potential, the research suggests. On top of that background factor, extreme events like droughts or torrential rains can destroy crops altogether. Extremes have always been part of the agricultural picture, of course, but they are expected to increase on a warming planet.

One of the new reports comes from Oxfam, the global antipoverty charity. It commissioned researchers at the Institute of Development Studies, at the University of Sussex in Britain, to use computer modeling to study the possible impacts of climate change on global food prices by 2030, compared with prices in 2010. (The Oxfam report is summarized here and can be downloaded here, and detailed methods and results can be found here.)

The researchers recognized that global food demand is rising as many millions of people in developing countries acquire the means to eat richer diets. That alone would be expected to drive food prices higher, but their calculations suggest that climate change will greatly compound the problem.

For instance, the report said that corn prices could jump by 177 percent, adjusted for inflation, by 2030, with stress from climate change accounting for something like half the increase. The price increases could be 120 percent for wheat and 107 percent for rice, with climate change accounting for perhaps a third of the increases for those crops.

And those are just the baseline price increases. Severe weather shocks could cause further spikes, induce panic buying, prompt countries to close their borders to food exports and even lead to riots and revolutions.

If any of that sounds alarmist, recall that every bit of it has already happened because of the price spikes of recent years. In 2008, food riots broke out in more than 20 countries, and the government of Haiti fell as a result of the unrest. The second price spike, in 2011, apparently played a role in the social discontent that led to the revolutions in the Arab world.

In the West, raw ingredients make up only a small fraction of the cost of the food most people eat, and price spikes tend to be felt only moderately for that reason. But in parts of the world where people subsist on staple grains, Oxfam warns, a doubling or more of grain prices from 2010’s already high levels would probably be devastating. The price spikes occurring over the last decade have already led to some of the biggest increases in global hunger in generations.

“Food price spikes are a matter of life and death to many people in developing countries, who spend as much as 75 percent of their income on food,” Oxfam said in its report. “Increased hunger is likely to be one of climate change’s most savage impacts on humanity.”

As many Green readers know, agriculture is not just a potential victim of climate change — it is also a major cause. It helps to drive extensive deforestation in the tropics, consumes fossil fuels and puts a powerful greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide, into the air.

So another new report, from researchers at the University of Minnesota, may prove especially interesting to anyone worried simultaneously about food security and the environment. It offers hope that both problems can be tackled at once.

This report, a scientific study published last week in the journal Nature, is also the result of computer modeling. The researchers asked whether it would be possible to increase global yields while reducing the use of agricultural inputs like water and fertilizers.

The basic finding is that overall output of 17 of the world’s most important crops could be increased by 45 to 70 percent by closing the “yield gap,” or the tendency of farmers in many regions to produce less than they could. And this could be done, the researchers found, while reducing the overall environmental harm from agriculture.

“We have often seen these two goals as a trade-off: We could either have more food, or a cleaner environment, not both,” the study’s lead author, Nathaniel D. Mueller, a doctoral student at the University of Minnesota, said in a statement. “This study shows that doesn’t have to be the case.”

The trick, the researchers found, would be to reduce inputs in some places where, for instance, nitrogen fertilizer is being applied too heavily (government subsidies often play a role) or water is being wasted. Conversely, more inputs and better farming methods are needed in regions where yields are far below potential.

The report found that the use of nitrogen fertilizer, the source of the nitrous oxide that is helping to warm the planet, could be cut by 28 percent without affecting yields for corn, wheat and rice, the world’s three most important grains. Use of phosphate fertilizer, the focus of fears about a long-term shortage, could be reduced by 38 percent, the researchers found.

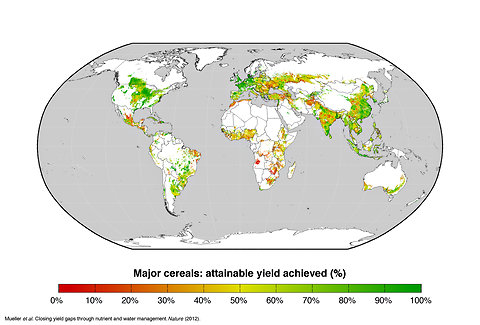

In the study, China stood out as a hot spot of excessive fertilizer use, while Eastern Europe and parts of Africa and India stood out as yield laggards where greater effort was needed. The map below shows regions of the world where farmers are meeting their potential, in green, and where they are falling short, in red.

Many organizations are working to change the situation, of course – the Rockefeller Foundation in New York has long been a stalwart of these efforts, joined in recent years by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the world’s largest charity.

Yet it remains to be seen whether world food production can be adapted quickly enough to head off a global supply squeeze that is even more severe than the one we have already experienced in recent years.

Nathaniel Mueller/.University of MinnesotaRegions of the world where food production approaches the highest practicable yields, shaded in green, and regions where output lags, in red.

Nathaniel Mueller/.University of MinnesotaRegions of the world where food production approaches the highest practicable yields, shaded in green, and regions where output lags, in red.

Article source: http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/06/climate-change-and-the-food-supply/?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.