Judith Scott-Clayton is an assistant professor at Teachers College, Columbia University.

A continuing refrain of Occupy Wall Street protesters has been “student debt is too damn high,” as James Surowiecki wrote in The New Yorker. In some cases — like for the college graduate profiled in a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education who has $100,000 in debt and uncertain job prospects — this is unarguably true. But such cases make for dramatic reading precisely because they are so rare.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

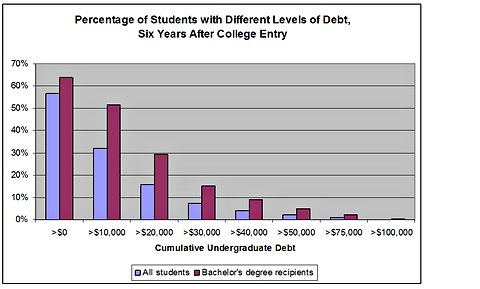

The first thing to note is that most of those with that much debt have graduate degrees; it is difficult to accumulate that much debt in an undergraduate program. The chart below shows the percentage of beginning undergraduate students who, six years later, had accumulated more than the indicated levels of debt.

Only one-tenth of 1 percent of college entrants, and only three-tenths of 1 percent of bachelor’s degree recipients, accumulate more than $100,000 in undergraduate student debt. If you have more than $75,000 in undergraduate debt, you are the 1 percent – just not the 1 percent you might have been hoping for.

U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2009)

U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2009)

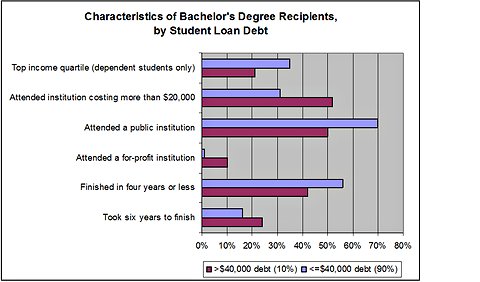

Even among recipients of bachelor’s degrees, 90 percent manage to graduate with less than $40,000 of debt. What happened to the other 10 percent is no particular mystery: they are less likely to come from wealthy families, but they attended pricier schools and paid for more years of tuition (see chart below). Compared with other graduates, these students are 20 percentage points more likely to have attended schools costing $20,000 or more a year (including room and board), and 20 percentage points less likely to have attended a public institution. Ten percent attended a private for-profit institution, compared with only 1 percent of their lesser-borrowing peers. High-borrowing students also took significantly longer to finish their degrees.

U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2009)

U.S. Department of Education, Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey (2009)

With a bachelor’s degree, even $40,000 may be a manageable level of debt over the long term. But for those who are unemployed – including 9.1 percent of the 20- to 24-year-old college graduate labor force and 20.4 percent of their peers with no college degree, according to a recent report – even much smaller amounts may be unmanageable in the short term.

Those who are struggling with their payments may be able to take advantage of deferments and forbearance provisions on the federal portion of their loans to help get them through the economic downturn. They probably should not hold their breath waiting for Congress to pass legislation forgiving all student loan debt, an idea some Occupy Wall Street protesters have advocated but which economists have panned.

In an effort to respond to this proposal, the Obama administration recently took several executive actions that will lower repayment burdens for some borrowers; for those enrolled in the income-based repayment plan, the changes could reduce monthly payments by a third.

Surprisingly, though, neither the protest movement nor the administration is talking about the imminent doubling of student loan interest rates. Congress temporarily reduced interest rates to 3.4 percent for subsidized loans originating in 2011-12, but beginning next summer the rate for new loans will rise to 6.8 percent.

I asked Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of Fastweb.com and FinAid.org, why there hadn’t been more pressure to extend the interest rate reduction, especially given that the government turns a net profit on its student loan programs. He noted that these profits help pay for Pell grants and other student aid programs and said that many student aid advocates feared that any extension of loan interest reductions would necessitate larger cuts elsewhere.

Given a choice between allowing interest rates to rise or cutting Pell grants, he said in an e-mail, “cutting the interest benefit is the lesser of two evils.”

This is probably true. Unlike changes in Pell grants, changes to the interest rate affect loan repayments years in the future, not students’ ability to pay for college now. And because the change only applies to new loans, many people most likely to be affected are primarily occupying high school classrooms, not Zuccotti Park.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=12bf8fa853872a34d0436a4ecf6317fd

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.