Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of the coming book “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Virtually all of the coverage of the debate over extending the temporary cut in the payroll tax has centered on the politics. Almost none has examined the economics of the issue. Indeed, it is nearly impossible to tell exactly why Republicans were so adamantly opposed to extending the tax cut. I’m still not sure.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

The first thing to know is that the payroll tax cut was not originally part of the $787 billion stimulus bill enacted in February 2009. Another tax cut, the Making Work Pay credit, was the principal tax cut in the legislation. It provided a $400 to $800 tax cut for every person or family with a positive tax liability and an income below $75,000 for individuals and $150,000 for couples.

The stimulus legislation also contained a number of other tax cuts for individuals and families that consumed 30 percent of the budgetary cost of the legislation. All tax provisions taken together, including those for businesses, added up to $326 billion – more than 40 percent of the total cost of the stimulus package, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.

At the end of 2010, all of the tax cuts enacted during the George W. Bush administration were scheduled to expire, as well as the Making Work Pay credit. Although President Obama wanted the tax cuts for the rich to expire on schedule, Republicans insisted on an all-or-nothing strategy. Republicans also asked that the Making Work Pay credit be replaced by a temporary two-percentage-point cut in the employees’ share of the payroll tax.

Cutting the payroll tax fit better with Republican economic theory, because the rate of taxation would be reduced. Tax credits, by contrast, which are subtracted directly from one’s tax liability, generally don’t affect economic decisions at the margin because tax rates are unchanged.

(Of course, the phasing in and phasing out of tax credits such as the earned income tax credit can have marginal rate effects. But Republican economic policy tends to ignore such effects and focuses almost exclusively on statutory tax rates.)

Since the beginning of the economic crisis, many Republican economists had insisted that a temporary payroll tax cut was the best possible stimulus, including the former chairmen of the Council of Economic Advisers, Michael J. Boskin and N. Gregory Mankiw, and the former director of the National Economic Council, Lawrence B. Lindsey.

Economists at Morgan Stanley predicted that the payroll tax cut would help power the economy to 4 percent growth in 2011. (Real gross domestic product growth has actually been less than half that rate.)

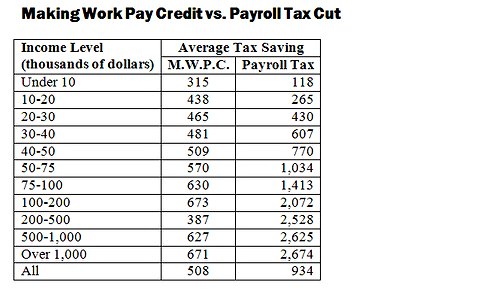

The following distribution table from the Tax Policy Center, on Dec. 14, 2010, shows more clearly why Republicans favored the payroll tax cut over the Making Work Pay credit – the benefits are much more skewed toward those with upper incomes.

It also shows why the Obama administration went along – the average tax saving was almost doubled, thus increasing the aggregate fiscal stimulus. The administration also thought the payroll tax cut would be more apparent to workers than the largely invisible Making Work Pay credit.

Tax Policy Center

Tax Policy Center

When the legislation was debated in the House of Representatives on Dec. 16, 2010, the House majority leader, Eric Cantor, pointed to the abolition of the Making Work Pay credit as a key reason why Republicans should support it.

In short, the payroll tax cut was a Republican initiative. So why did they turn against it? The answer is unclear.

To be sure, some Republicans were unenthusiastic about the payroll tax cut in the first place, as were some Democrats who feared damage to the Social Security trust fund. (The Treasury has reimbursed the trust fund for the lost payroll tax revenue.)

As early as last summer, Republican leaders began trashing the payroll tax holiday. House Speaker John Boehner called it a short-term gimmick and Paul D. Ryan, chairman of the House Budget Committee, branded it “sugar-high economics.”

In August, The Wall Street Journal editorial page came out against extending the payroll tax cut. A Heritage Foundation study in September argued that it was ineffective because it was oriented toward average workers rather than wealthy job creators.

Yet, there is precious little evidence that the payroll tax holiday did much, if anything, to stimulate growth or job creation. The Congressional Budget Office rated it as among the least stimulative fiscal policies. Some economists have argued that the Making Work Pay credit provided more bang for the buck.

In the end, economic arguments had little to do with how the payroll tax cut extension played out.

Republicans were in a weak position arguing against it because, historically, they have never opposed any tax cut, no matter how ill-designed or costly. And it was too easy for Democrats to press their political advantage, even though many had doubts about the efficacy of the payroll tax cut.

Sadly, we will probably go through the same exercise this time next year.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=4aefc03ce4240d2f93165b267e58d393

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.