Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

In recent weeks, the odds favoring tax reform in the not-too-distant future have improved somewhat.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

The improving deficit means that tax reform need not raise net revenues, as President Obama has demanded; the controversy about aggressive tax avoidance by Apple and other multinational companies has focused Congress’s attention on a key goal of tax reform, which is fixing the multinational tax regime; and the furor over the Internal Revenue Service and accusations that it targeted conservative groups almost certainly means there will be bipartisan legislation to make sure this doesn’t happen again, thus providing a legislative vehicle for tax reform.

What is missing, unfortunately, is the outline of an actual tax reform bill. Some progress, however, has been made.

The Joint Committee on Taxation has recently published a 568-page report on various tax reform options based on the work of House Ways and Means Committee working groups. The committee has even released draft tax reform legislation involving financial derivatives, small businesses and the international sector.

The Senate Finance Committee has released a number of tax reform options papers related to family taxation, business investment and innovation, international competitiveness and other topics. Many insiders also believe that the recently announced retirement of the committee’s chairman, Senator Max Baucus of Montana, improves the prospects for tax reform because his precarious position as a Democrat from a heavily Republican state limited his ability to lead a contentious debate on the subject.

Almost everyone agrees that the ultimate goal of tax reform should be to lower statutory tax rates and that it should be revenue-neutral, that is, neither raising nor lowering net federal revenues over some reasonable time period. This will require the elimination of many tax expenditures benefiting both individuals and businesses.

But at present, no one has put a single specific, significant tax expenditure on the table for elimination, and that is the rub. The tax reform bills that have been introduced thus far are mostly grandiose, utopian plans to completely replace the entire tax system; they have no chance whatsoever of enactment.

In public discussions of tax reform, commentators and politicians tend to blithely assume that all tax expenditures are equivalent to tax loopholes – illegitimate provisions of the tax code that benefit only special interests. But as I have explained previously, all of the really large tax expenditures benefit broad segments of the population or are regarded as legitimate components of the federal tax system that serve vital national interests, like home ownership, helping people save for retirement or providing them with health insurance.

To be sure, many tax loopholes cannot be defended. But they tend to be small and do not provide much revenue to pay for more than a trivial reduction in tax rates.

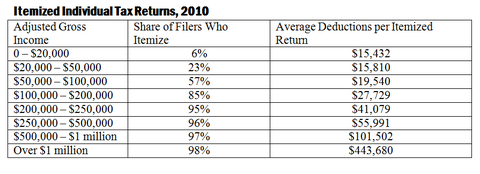

One problem for tax reformers is the disparate impact of specific tax deductions on different people. For starters, only about a third of tax filers itemize; the rest use the standard deduction. Among those that itemize, those with high incomes are much more likely to do so than those with more modest incomes. This fact is illustrated in the following table from a recent Congressional Research Service report.

Congressional Research Service analysis of Internal Revenue Service Data

Congressional Research Service analysis of Internal Revenue Service Data

Moreover, use of certain deductions depends on one’s income. For example, the very wealthy get little value from the mortgage interest deduction because the law limits it to mortgages of less than $1 million. But the wealthy are much more likely to use the charitable contributions deduction and to deduct large amounts. The average charitable deduction for those with incomes above $1 million was almost $140,000 in 2010.

Consequently, ending or restricting particular deductions will have very different economic and distributional effects at different income levels. Some of these effects are reviewed in a May 21 report from the Congressional Research Service.

The report notes that the most commonly discussed option for raising revenue by restricting itemized deductions wouldn’t abolish them entirely but would limit their availability in some way. The total amount of deductions claimed could be limited by a dollar amount, they could be limited to a certain percentage of income, there could be floors that allow deductions only over a certain amount and various other schemes.

One problem is that phasing out deductions in some way creates disincentives equivalent to raising marginal tax rates. According to the report, simply eliminating all itemized deductions would be equivalent to raising the top income tax rate by 4.4 percentage points. Eliminating the deductions for state and local taxes or for charitable contributions is equivalent to raising the top rate by 2.2 percentage points.

This means that even if statutory rates are simultaneously reduced, there may not be any reduction in effective marginal tax rates, depending on what deductions are restricted or eliminated and how it is done. Only careful analysis can determine the net impact of any particular proposal.

This is why it is essential to have a detailed tax reform plan to analyze. Vague talk about broadening the tax base and lowering statutory tax rates is insufficient to guide legislation. And it takes more time than most people imagine to work through all the effects of various tax reforms, especially when many provisions of the tax code are being changed simultaneously that may move in opposite directions, economically.

Thus far, the Obama administration has been disengaged from the tax reform effort. But if it is going to happen, this must change. That is one lesson of previous tax reform efforts in 1969, 1976 and 1986, all of which were guided into enactment by strong Treasury Department leadership.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/28/getting-to-tax-reform/?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.