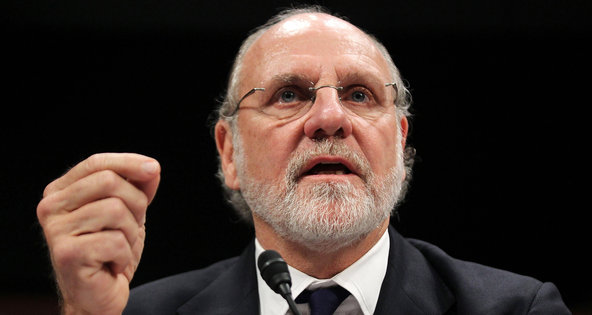

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesJon Corzine, former chief of MF Global, at a House panel in 2011.

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesJon Corzine, former chief of MF Global, at a House panel in 2011.

Under pressure from regulators last summer to increase its capital cushion, MF Global moved some of its risky European debt holdings to an unregulated entity in an effort to avoid having to raise extra money, according to a new report. The revelation raises new questions about MF Global’s actions in its last months — in particular, how it responded to regulators. The brokerage firm had previously disclosed that it had met the capital requirements, but never mentioned that it had transferred some bonds rather than raising additional money. The shift was detailed in a report by Louis J. Freeh, the trustee overseeing the bankruptcy of MF Global. The report is separate from the one issued Monday by James W. Giddens, the court-appointed trustee charged with recovering money for MF Global’s customers.

Related Links

“This strategy allowed the MF Global Group to transfer the economic benefits and risks,” thus reducing the “regulatory capital requirements,” the report by Mr. Freeh said.

Shifting the bonds to an unregulated entity to avoid capital requirements is unusual at financial firms, corporate accounting specialists say. Regulators expressed concerns about the maneuver, although ultimately they did not block it. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Wall Street’s self-regulator, said it lacked jurisdiction to pursue the matter further.

“It’s a shell game, and the problem is the regulators buy off on this stuff, and then when it implodes, they always look so stupid,” said Lynn E. Turner, the former chief accountant at the Securities and Exchange Commission. “Common sense says why would you accept these types of shenanigans?”

The new details are part of Mr. Freeh’s 119-page report outlining the status of his investigation of MF Global, which collapsed last October after misusing roughly $1 billion of customer money. In the report, which was filed in Federal Bankruptcy Court in New York late Monday, Mr. Freeh said that creditors such as banks and big investors could have more than $3 billion in claims against the company.

“This report gets to the heart of the complex intercompany relationships inherent in a global firm that provided financing for its affiliates and subsidiaries all over the world,” said Mr. Freeh, a former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. “We believe this report provides increased transparency as to how the firm’s capital flowed through these entities.”

Mr. Freeh, who is responsible for recovering money on behalf of MF Global’s creditors, has cast a worldwide net. The report lists claims against affiliates from Britain to Mauritius. But Mr. Freeh’s biggest potential target is Mr. Giddens, the trustee whose job is to return customers’ missing money.

Mr. Freeh has filed claims for more than $2.3 billion against a separate dealer entity that Mr. Giddens is overseeing, drawing the lines in an increasingly tense turf war between the men.

Ultimately, their missions — to claim a limited pool of money — are at odds. Mr. Giddens is working to get money from that pool for farmers, traders and hedge funds left with a roughly $1 billion hole in their accounts. Mr. Freeh is vying for much of the same funds, but on behalf of businesses and banks that are owed money by MF Global.

While publicly the men have played down tensions between them, privately the fight has become more acrimonious. Mr. Freeh’s report is littered with references to Mr. Giddens’s office not producing documents and information.

The tension could have affect customers. Mr. Giddens is expected to set aside a substantial amount of money because of Mr. Freeh’s claims, which would “take those assets out of the pool available for distribution to customers until the claims are resolved,” said Kent Jarrell, a spokesman for Mr. Giddens.

Mr. Giddens released his own status report earlier Monday. The 275-page document covered in painstaking detail the final weeks before MF Global’s collapse, and raised the prospect of filing civil suits against top executives at the firm to recoup assets, including the former chief executive, Jon S. Corzine.

The report provided the most exhaustive accounting yet of what transpired at the firm, including its decision to tap customer money with repeated frequency as the business suffered a crisis of confidence.

What the reports from Mr. Freeh and Mr. Giddens have in common is the portrait they paint of MF Global and its leadership. The firm that emerges from their pages is one that was constantly flying by the seat of its pants, prone to risky decisions with few controls to keep it in check. While the chaos in the last days of the firm is well known, what the reports show is that aggressive behavior was taking place well before the market took its toll.

Mr. Freeh is still conducting an investigation of what happened at the commodities brokerage firm. Yet, the details on MF Global’s efforts to skirt capital rules raise additional questions about what the firm — and its regulators — were doing to address a looming crisis.

Months before MF Global filed for bankruptcy, regulators raised concerns about the firm’s $6 billion bet on European sovereign debt. At the time, worries about highly indebted nations like Greece, Spain and Italy were causing volatility in the financial markets.

Given the market turmoil, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or Finra, demanded that MF Global set aside extra money in case the trades soured. But MF Global objected, appealing the regulator’s ruling to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Mr. Corzine, the former Democratic governor of New Jersey and a former head of Goldman Sachs, lobbied the S.E.C. to back down, flying down to Washington from New York to make his appeal in person.

He lost. The agency sided with Finra. In a September 2011 filing, MF Global said it had “increased its net capital and currently has net capital sufficient to exceed both the required minimum level and Finra’s early-warning notification level.”

But the disclosure did not give the full picture. While MF Global did move some cash around to protect against losses, the firm also transferred roughly $3 billion in holdings of Italian bonds from its brokerage arm to “FinCo,” an unregulated entity of the firm, according to Mr. Freeh’s report. By doing so, MF Global met its requirements without having to raise money.

At the time, MF Global held about $6 billion in the debt of Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal, representing about 14 percent of its assets and nearly five times the equity of the firm. The Italian bonds represented about half the firm’s risky European position.

After Finra’s capital request became known in October, investors were rattled, pushing the shares of MF Global sharply lower. Ratings agencies warned that they might cut the firm’s credit ratings, escalating the fears in the marketplace. The effect of downgrades from Moody’s Investors Service and Standard Poor’s were worsened by a poor earnings report. On Oct. 31, MF Global filed for bankruptcy.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/06/05/mf-global-dodged-capital-requirements-study-says/?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.