Jason Delisle is the director of the Federal Education Budget Project at the New America Foundation.

In his State of the Union address, President Obama proposed to expand access to preschool, but offered few details on how much money the federal government would contribute. When the White House eventually releases that figure, everyone will want to know how it stacks up against what the federal government already spends on education each year. The trouble is, that number is tough to pin down.

You might try to look it up. But beware: most tallies, even official government figures, are incomplete or inaccurate because of the way they treat student loans, refundable tax credits and education programs run by agencies other than the United States Department of Education. Other tallies go too far, lumping veterans’ education benefits and other programs into the mix.

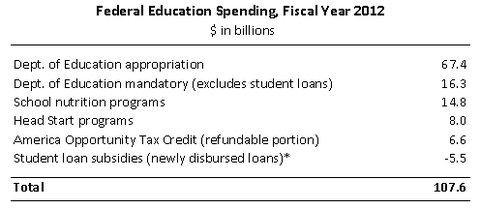

Before explaining how to get to a good number, I’ll give you mine. The federal government spent $107.6 billion on education in fiscal year 2012. As a point of reference, that sum is about one-eighth as much as Social Security spending and about a fifth of Medicare spending. Most of our national education budget comes from state and local governments. But the $107.6 billion provides a dose of perspective for when federal policy makers pledge to “invest in education” and make education a “top priority.” Federal education spending accounts for just 3 percent of the $3.5 trillion the government spent in 2012.

The figure includes the annual appropriation for the entire Department of Education ($67.4 billion), so-called mandatory spending at the department ($16.3 billion), the school breakfast and lunch programs ($14.8 billion), the refundable portion of a higher education tax credit ($6.6 billion), the Head Start program ($8.0 billion) and the subsidy provided on all of the student loans the government will disburse in one year (which happened to be negative — -$5.5 billion — last year).

*Congressional Budget Office fair-value estimate for fiscal year 2013 cohort.

*Congressional Budget Office fair-value estimate for fiscal year 2013 cohort.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture, President’s Fiscal Year 2013 Budget Request, Congressional Budget Office, New America Foundation Federal Education Budget Project

The annual appropriation for the Department of Education is an obvious figure to include, but as you can see, education spending includes a significant amount outside annual appropriations, much of which goes to support the Pell Grant program for college students from low-income families.

The school meal programs are less obvious components, but should be included. The programs help ensure that more than 31 million children each year do not go hungry at school, a prerequisite for good educational outcomes. Surely when a local district builds a new school it doesn’t consider the cafeteria an optional line item tangentially related to the school’s purpose. Feeding children during the school day is, in fact, integral to their education.

Similarly, the Head Start program, although housed in the Department of Health and Human Services, is a national preschool program dedicated to early education. When people think of federal education spending, Head Start often comes to mind.

The federal government also provides a long list of tax benefits (i.e., credits, exemptions and deductions) to support education. They totaled $33.2 billion in 2012 by one count, but I’ve excluded them in the spending tally. Experts argue over whether tax benefits are part of federal spending policy or tax policy. No funds leave the Treasury to finance these programs; instead, funds fail to arrive as revenue in the first place. Others argue that the benefits are not different from spending because a $1,000 tax credit has the same bottom-line effect on the federal budget as a $1,000 grant.

A “refundable tax credit” is, however, a different matter. No one debates the fact that a refundable tax credit is government spending. The recipient owes no taxes but receives a refund check as if he did. He pays negative federal income taxes. Even the Treasury Department treats the payments as “outlays.” Last year the government spent $6.6 billion in refundable payments under the America Opportunity Tax Credit, which I include in my measure of education spending. Tax filers can claim up to $1,000 of the credit against expenses for higher education, even if they have no tax liability to offset.

Finally, the federal government disbursed $112 billion in student loans in 2012. Most of that will be paid back, with interest. So what does the government spend on the loans? The government measures the cost of its loan programs by the subsidy that they provide to the borrower. Put simply, if the government lends at very favorable terms, then the borrower receives a subsidy equal to the discount the borrower received relative to a loan he or she otherwise could have taken out. Even though the benefit is spread over the life of the loan, this calculation treats the subsidy as one lump sum in the year that the loan is made.

By that measure, official figures show that the government’s student loan programs provide negative subsidies, which is to say, interest rates and fees are set high enough that the government makes money. But there is a big flaw with those figures.

The Congressional Budget Office and many economists argue that official figures don’t factor in all of the risks inherent in the loans. In response, the Congressional Budget Office publishes fair-value estimates to more fully reflect risk, and I use those figures in my tally of federal education spending. Note that even after the adjustment, the one year’s worth of loans still show a net gain to the government of $5.5 billion.

Excluded from my tally are any of the education benefits provided through the Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs. Funds for those programs should be considered military and veterans’ spending rather than federal education spending. The benefits are part of the compensation packages that the government provides to support an all-volunteer military. Similarly, a housing allowance for a member of the military is not a federal housing assistance program. The benefits are in-kind costs associated with financing the military. If included, those programs would add more than $10 billion to the $107.6 billion total.

The $107.6 billion figure, despite excluding military and veterans’ programs, reflects a more comprehensive measure of federal education spending than most. Even so, it is probably surprising to many that education spending comes in at just 3 percent of the $3.5 trillion the federal government spent in 2012. It is hardly the figure that comes to mind when a lawmaker or the president speaks of investments and priorities.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/27/putting-a-number-on-federal-education-spending/?partner=rss&emc=rss