CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

Three of every five cigarettes consumed in New York State were smuggled in from lower-tax states in 2011, according to new estimates from the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a free-market research organization in Michigan. That is the highest smuggling rate in the country.

Perhaps not coincidentally, New York State also has the highest cigarette tax rate — $4.35 per pack, not counting the additional $1.50 per pack levied in New York City.

New Hampshire had the highest share of its cigarettes — 26.8 percent — smuggled out of the state. The state cut its tax rate in 2011 by 10 cents to $1.68, still slightly higher than the national average. But it is surrounded by states with much higher tax rates. In Massachusetts, for example, the tax was $2.51 per pack.

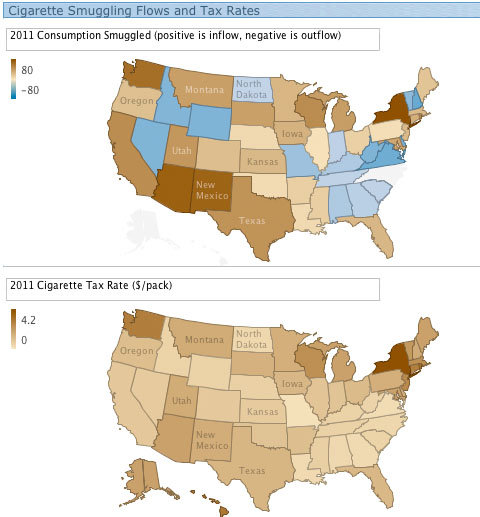

Below you can see maps showing where the most smuggling occurs and what the relative tax rates are.

Sources: Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Tax Foundation. In the top map, rates are in percentage terms. Note: Smuggling rates are not available for Alaska, Hawaii, North Carolina and the District of Columbia. Cigarette tax rates have changed for some states since 2011. Map created using Many Eyes.

Sources: Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Tax Foundation. In the top map, rates are in percentage terms. Note: Smuggling rates are not available for Alaska, Hawaii, North Carolina and the District of Columbia. Cigarette tax rates have changed for some states since 2011. Map created using Many Eyes.

In the top map, which shows percentages for smuggling rates, positive numbers mean that there was a net inflow of cigarettes (i.e., more cigarettes were smuggled in than out), and negative numbers indicate that there was a net outflow. The bottom map shows the state tax per cigarette pack, in dollars.

The Mackinac Center also has data comparing tax and smuggling rates from 2006 to 2011, by which time most states had raised their cigarette taxes in an attempt to collect more revenue. New York State almost tripled its tax rates during that time, but smokers appeared to respond by buying more of their cigarettes across state lines.

It’s not clear that New Hampshire’s decision to cut its tax rate to capture more out-of-state customers, on the other hand, was any more profitable. That’s partly because within 24 hours of the state’s 10-cent cigarette tax cut, cigarette manufacturers raised their own prices by 10 cents.

(These data were reformatted, I should add, by the Tax Foundation, a conservative-leaning research organization in Washington.)

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/10/cigarette-taxes-vs-cigarette-smuggling/?partner=rss&emc=rss