Any time the stock market hits a new milestone, whether it’s going up or down, we start to hear a lot of noise. And the chatter seems to be focused on this idea of what it all means.

With the Dow hitting new highs, the noise has become so pervasive that, by default, there’s the implication we should all be doing something or at least thinking about it. In fact, the number one question I’ve been asked recently is some variation of, “Should I get in or out of the market?”

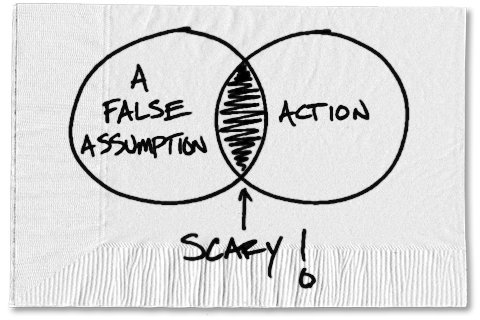

When we’re reading and hearing this stuff, it is incredibly important to understand that the issue is far more subtle than getting in or getting out of the market. Because built into that question is the potential for a false assumption, and it’s a risky one: You don’t already have a plan.

Now, if you’re one of the rare individuals sitting on a big pile of cash — maybe you just sold your business or received some other lump-sum settlement — the question of getting in the market might matter to you.

But most of us already have a plan (though that may be a false assumption, too). We’re already invested. And if it’s a well-crafted, diversified plan based on the things we value, then the assumption that timing should matter to you can lead us to ask other timing questions, like:

- Should I still add to my 401(k)?

- Since it’s tax time, should I make my annual contribution to my profit sharing account, SEP or IRA?

- Should I still rebalance?

If you’re already invested and have a plan, the answer to all of these questions is the same. If it was part of your plan to do any of these things, you should still do it.

I understand that it’s hard, and that it feels like we should be doing something. But it’s important for us to understand that when we make important financial decisions based on a false assumption, it can lead to scary results.

So the next time (or even this time) the noise implies that you should be doing something — because the markets are doing something — it’s time to check your assumptions. The noise probably doesn’t apply to you.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/11/market-milestones-can-lead-to-false-assumptions/?partner=rss&emc=rss