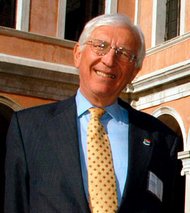

Andrea Merola/European Pressphoto AgencyDavid Walker

Andrea Merola/European Pressphoto AgencyDavid Walker

Will Oliver/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesMarcus Agius, the outgoing chairman of Barclays.

Will Oliver/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesMarcus Agius, the outgoing chairman of Barclays.

LONDON — Barclays, whose top management was toppled amid an interest rate manipulation scandal, on Thursday turned to a former Bank of England official to be its next chairman.

The British bank has named David Walker, 72, a longtime London banker and former official of the central bank and the British Treasury, to be chairman, replacing Marcus Agius. Mr. Agius and other senior executives of Barclays, including its chief executive, Robert E. Diamond Jr., resigned last month during an investigation into the manipulation of the London interbank offered rate, or Libor.

Mr. Walker’s first major task when he takes over in November will be to lead the search for a replacement for Mr. Diamond.

With the appointment of a new chairman, Barclays is hoping to draw a line under the Libor scandal, which has raised questions about the governance and culture at the British bank. Senior British officials had raised questions about the management style of Mr. Diamond, with concerns dating to his appointment to the top spot in late 2010, according to documents released by the Bank of England.

Revolving Door

View all posts

Scrutiny of Mr. Diamond and the firm’s governance came months — and in one case, years — before Barclays came under fire for trying to manipulate key interest rates.

Mr. Walker has decades of experience that he will have to draw upon for the new role.

He has led government-mandated reviews into practices of the country’s financial services industry, as well as an inquiry into the Royal Bank of Scotland, which is 82 percent owned by the government after receiving a bailout during the financial crisis.

He has called on banks to disclose more information about the bonuses that they pay top executives, and is well respected within the industry as a corporate governance expert.

“David commands great respect within the financial services industry and will bring immense experience, integrity and knowledge to the role,” Mr. Agius said in a statement.

Mr. Walker is the former chairman of Morgan Stanley International, and currently holds a senior adviser position at the American bank. He also has held senior posts at the Lloyds Banking Group and the pension firm Legal and General.

As part of the transition, Mr. Walker will become a nonexecutive director at Barclays at the beginning of September, before assuming the chairmanship later this year. While the bank continues to search for a new chief, it is unlikely that a final decision will be made on who will take over the top spot until Mr. Walker assumes his responsibilities.

The British bank has moved quickly in finding a replacement for Mr. Agius, who was the first Barclays executive to resign over the Libor scandal.

After agreeing to a $450 million settlement with American and British authorities in late June in connection with the manipulation of Libor, Barclays has remained under fire from politicians on both sides of the Atlantic.

Local regulators have highlighted problems with the firm’s corporate governance, including efforts to avoid paying about $770 million in taxes, and questioned some of the bank’s accounting methods.

“Barclays often seems to be seeking to gain advantage through the use of complex structures, or through arguing for regulatory approaches, which are at the aggressive end of interpretation of the relevant rules and regulations,” Adair Turner, chairman of the Financial Services Authority, the country’s regulator, said in the letter to Mr. Agius earlier

An earlier version of this post misstated the age of David Walker. He is 72, not 73.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/08/09/barclays-names-a-new-chairman/?partner=rss&emc=rss