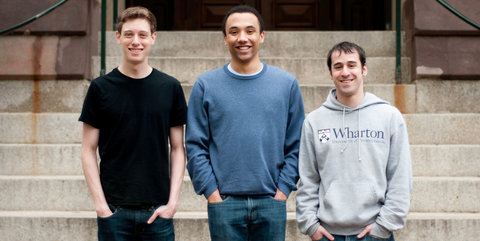

Courtesy of the Dorm Room Fund The founders of Firefly got financing from the Dorm Room Fund.

Courtesy of the Dorm Room Fund The founders of Firefly got financing from the Dorm Room Fund.

Start

The adventure of new ventures.

Most college dormitories are a mixture of unmade beds, fireproof carpeting, beer pong, ramen noodles and that poster of John Belushi in “Animal House.” Investors want to add two more ingredients: successful start-ups and budding venture capitalists.

“We’re trying to help students feel what it is to run a start-up, to take an idea that starts in a dorm room with a bunch of friends and move it out to the market, into the hands of real customers, and hopefully learn what it feels like to build something people really love,” said Phin Barnes, a partner at the venture firm First Round Capital, which is based in Philadelphia.

In September, First Round started the Dorm Room Fund, putting $500,000 in the hands of an 11-member investment team of college students from the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University. The board has already considered some 200 student-led ventures in the Philadelphia area and selected six for investments averaging $20,000 apiece. The recipients include Firefly, a developer of co-browsing customer support software, and Dagne Dover, a handbag and accessories brand. And starting this spring, First Round is taking the Dorm Room Fund nationwide.

“When we launched in Philadelphia, we asked students to reach out to us if they wanted Dorm Room Fund to come to their cities or schools,” said CeCe Cheng, the fund’s director. “The New York universities had an overwhelming response.”

Applications for a new student-led investment team in New York City closed on March 11. Slots were limited to candidates from Columbia University, Cornell Tech Campus, New York University and Princeton University, though students at any college in the region will be eligible for funding.

New York City’s Dorm Room Fund will follow the model established in Philadelphia, Mr. Barnes said. Student investors will seek out promising ventures among their peers and present the most exciting projects to the investment team. Though partners from First Round Capital will offer advice, students will lead the decision-making process. First Round does retain a veto right, Mr. Barnes said, but “we would not use it unless we were legally or ethically required to do so.”

The Dorm Room Fund also plans to create an outpost in the Bay Area, with two or three additional cities to follow later this year. If all goes according to plan, members of each investment group will eventually pick their own successors. But for now, it’s up to the folks at First Round to assemble the teams.

“One of the things that we look for in interviews is people who are really curious about start-ups and technology,” Mr. Barnes said. Advanced knowledge of finance is not required, but experience starting new ventures or developing other independent projects is an asset. Team members are expected to keep building their skills through coaching and experience. First Round also wants each investment team to represent a range of fields and include students from both graduate and undergraduate programs.

The “by students, for students” idea has seen a recent surge in popularity. A few months after First Round Capital started the Dorm Room Fund, the investment firm General Catalyst announced Rough Draft Ventures, a student-run investment fund in Boston making $5,000 to $25,000 investments in college entrepreneurs. And the Boston region already had something similar: The Experiment Fund — capitalized by Accel Partners, New Enterprise Associates and Polaris Venture Partners — which set up shop in Cambridge early last year and included a Harvard graduate student on its investment team.

Student-run funds have been popular for more than a decade, but most have been hosted by individual universities to finance a range of start-ups, rather than investing exclusively in student-led ventures. The University of Michigan’s $5.5 million Wolverine Venture Fund started in 1999 and calls itself the nation’s first student-run venture capital fund; the University of North Dakota’s Dakota Venture Group, founded in 2006, lays a similar claim. At Cornell University’s Johnson School of Management, M.B.A. students have been running BR Ventures – the letters stand for “Big Red” and refer to Cornell’s sports teams – since 2001, when alumni donated $1.2 million to endow the fund.

The current wave of student venture financing comes at a time when higher education skeptics are urging teenage dreamers to skip college altogether and head straight for Silicon Valley. Since 2011, their most prominent figurehead – Peter Thiel, the libertarian billionaire and co-founder of PayPal – has awarded $100,000 to 40 ambitious young entrepreneurs to do just that.

The Dorm Room Fund does not require recipients to drop out of school. “I think part of this whole mentality is people watch ‘The Social Network’ and they think, ‘I’ll drop out and raise a bunch of money, move to Silicon Valley and spend two years building a start-up. It’ll get really big, then I’ll exit and just sit around,’” said Dan Shipper, 21, a University of Pennsylvania junior who — along with co-founders Patrick Leahy and Justin Meltzer — started Firefly, the inaugural Dorm Room Fund company.

“That’s not how we think,” he added. “We’re going to be doing this for a really long time. This is how we want to spend our lives. We’ve always had a mentality of concentrating on revenue and getting paying customers first, then thinking about raising money later.”

The Dorm Room Fund’s $20,000 investment, he said, was the right size for Firefly – “not so much money that we get fat and lazy” – but enough to hire a summer intern, run more servers and do some marketing.

And staying in college has its perks. “I’m a philosophy major,” Mr. Shipper said, laughing. “I’m not in school because I’m going to get high-paying work in philosophy. But I find it valuable and it’s meaningful to my life.”

You can follow Jessica Bruder on Twitter.

Article source: http://boss.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/02/a-start-up-fund-that-lets-college-students-make-the-decisions/?partner=rss&emc=rss