Laura D’Andrea Tyson is a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and served as chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Bill Clinton.

According to the last jobs report for 2012, the United States labor market continues to recover at a steady but modest pace despite a global slowdown, Hurricane Sandy and anxieties about future fiscal policy. Private payrolls increased by two million in 2012, and the unemployment rate fell by 0.7 percentage point to 7.8 percent. Over the last 34 months, the economy has added 5.8 million jobs.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

But that leaves a four million shortfall in employment relative to its 2007 peak. And the jobs gap, the number of jobs necessary to return to this peak and cover the growth in the labor force since then, is stuck around 11 million. The labor market is still far from full recovery, with a tremendous waste of human talent and a personal toll on unemployed workers and their families.

This year is likely to be more of the same, as the deal on the fiscal cliff — the American Taxpayer Relief Act — will take about 0.4 to 0.6 percent off the economy’s growth rate.

Additional cuts in government spending later this year, above those already emanating from the cap on discretionary spending, would further restrain job creation. Proven policies to increase aggregate spending and near-term job growth, like the continuation of payroll tax relief and infrastructure investment, appear to be off the table. That’s a mistake, because weak demand and slow growth of gross domestic product are the primary factors behind the tepid pace of job creation.

Despite anecdotes about how employers cannot find workers with the skills they need, there is little evidence that the unemployment rate remains elevated because of mismatches between the skill requirements of available jobs and the skills of the unemployed.

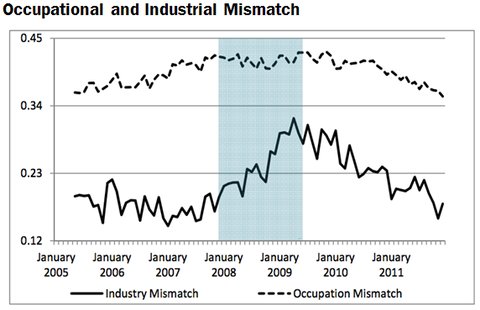

When the recession hit in 2008, unemployment rates soared in every industry. As usual during recessions, mismatches between employer needs and worker skills also increased temporarily, reflecting greater churn in the labor market as workers were forced to move across industries and occupations.

But industrial and occupational mismatch measures are now back to their prerecession levels, indicating that the overall unemployment rate is high because unemployment rates remain high across all industries and most skill groups, not because of a growing skills gap relative to the gap that existed before the recession.

Edward P. Lazaer and James Spletzer, “The United States Labor Market: Status Quo or a New Normal?” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2012, with data from the Conference Board.

Edward P. Lazaer and James Spletzer, “The United States Labor Market: Status Quo or a New Normal?” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2012, with data from the Conference Board.

The unemployment rates for all workers at all education levels jumped during the recession and have not recovered to prerecession levels. Even before the recession, the unemployment rates for workers with a high-school education or less were much higher than those for workers with a college education or higher. And there were high vacancy rates and low unemployment rates for professional occupations, while many service and blue-collar occupations had low vacancy rates and high unemployment rates. These structural differences persist but are no larger than they were before the recession.

Increases in educational attainment levels and effective training programs would ameliorate such differences and the growing wage inequality they have generated. They would also facilitate the movement of workers among industries and occupations, making the labor market work better and reducing the structural unemployment rate from industrial and occupational mismatches.

Alas, state funds for such programs have been slashed and federal funds will probably get an additional haircut later this year, even if the debilitating cuts in the sequester are averted as part of a long-run budget deal.

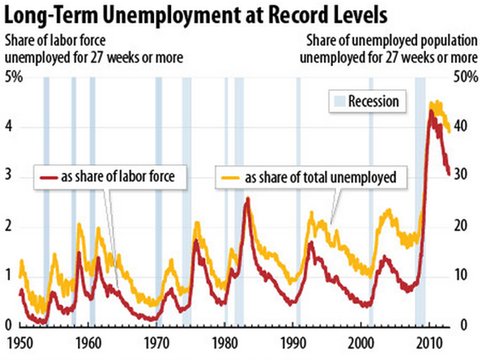

Another feature of the current recovery is the long duration of unemployment for many workers. At the end of last year, 4.8 million Americans were unemployed for 27 weeks or more, and their share in the total number of unemployed workers fell to 39 percent after peaking at 45.5 percent in March 2011 and exceeding 40 percent for 31 consecutive months. The previous peak was a far lower 26 percent in 1983, at a time when the unemployment rate was about as high as it is now.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, using data from Bureau of Labor Statistics and National Bureau of Economic Research

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, using data from Bureau of Labor Statistics and National Bureau of Economic Research

Moreover, the number of workers who are grappling with long-term job loss is probably far larger than the official number of long-term unemployed, as it does not include 1.1 million discouraged workers who want a job but are not currently looking for work, and many of the 1.7 million workers who have joined disability rolls because they cannot find a job.

Why is the long-term unemployment problem so much more severe in this recovery? Part of the answer lies in the fact that the loss of jobs in the 2008-9 recession was more than twice as large as in previous recessions and the pace of gross domestic product growth during the recovery has been less than half the average of previous recoveries.

The relationship between the vacancy rate and the unemployment rate — the so-called Beveridge curve — suggests other forces are at work as well. When the vacancy rate rises, the unemployment rate usually falls along a path that has remained quite stable over long periods of time, including the 2001 recession and subsequent recovery.

But a recent study finds that during the current recovery the normal relationship has broken down for the long-term unemployed — the increase in the vacancy rate has produced a smaller-than-expected decline in the long-term unemployment rate. In contrast, the usual relationship between the vacancy rate and the unemployment rate has held for those unemployed for fewer than 27 weeks.

There are several reasons that the long-term unemployed are not benefiting as much as the short-term unemployed from the increase in job vacancies as the economy recovers. Many long-term unemployed may not have the qualifications required for posted job vacancies, and the longer they are unemployed, the more their skills become obsolete and their actual or perceived employability erodes. To make matters worse, the longer workers are unemployed, the more skeptical employers become about their employability and work habits. Another recent study found that the likelihood that a job applicant receives a call-back for an interview significantly decreases with the duration of his or her unemployment.

In addition, many jobs are filled through contacts and informal networks, and the longer workers are unemployed, the weaker their contacts with potential employers and the less information they have about job opportunities.

Some long-term unemployed may also be searching less intensively or may be less willing to accept job offers during this recovery, in part because good jobs are so much harder to find and because unemployment benefits last longer and are more generous than in previous recoveries.

During his first term, President Obama proposed several initiatives to reduce long-term unemployment, including more flexibility for states to use unemployment funds for training and placement programs, a tax credit to businesses to hire workers out of a job for more than six months, and an $8 billion fund to support training and job placement at community colleges.

These programs failed to win Congressional approval, and they have dropped out of the debate as Washington’s focus has shifted from job creation to debt reduction.

The economic evidence is compelling. The high unemployment rate is the result of weak demand, not structural mismatches. And the longer workers are unemployed, the more their skills, contacts and links to the labor market atrophy, the less likely they are to find a job and the more likely they are to drop out of the labor force.

As a result, what is currently a temporary long-term unemployment problem runs the risk of morphing into a permanent and costly increase in the unemployment rate and a permanent and costly decline in the economy’s potential output. That’s what the Federal Reserve is worried about. It’s too bad that more members of Congress don’t share this concern.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/11/why-the-unemployment-rate-is-so-high/?partner=rss&emc=rss