Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform — Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

For most people, the sum total of their opinion about taxes is very, very simple: they hate them — not just the tax payment, but the act of paying taxes: pulling together the information needed to do one’s tax return, filing it, worrying about being audited for some small error and so on.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

These attitudes are confirmed in a new compendium of public opinion on taxes published by the American Enterprise Institute. The editors, Karlyn Bowman and Andrew Rugg, tell us:

In 75 years of surveys, we can find no instance in which more than a tiny percentage of Americans said the amount they paid in taxes was too low. In most polls, pluralities or majorities say the amount is too high.

But the data do suggest that the percentage of people who think their taxes are too high has declined over time. Until the early 2000s, that figure was commonly in the three-fifths to two-thirds range, but it has since trended down to about 50 percent. Conversely, the percentage of people saying their taxes are about right has risen to where in some polls it sometimes exceeds the percentage saying that taxes are too high.

Conservatives like to argue that the greatest unfairnesses of the tax code are that the wealthy are taxed at higher rates and that close to half of those who file income tax returns have no tax liability. But polls indicate that most people believe that the greatest unfairness in the tax system is that the wealthy do not pay their fair share.

A poll in April 2003 sponsored by National Public Radio, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Kennedy School of Government found that 57 percent of people believed that high-income families paid less than their fair share. A December 2011 Pew poll found the same percentage saying so. By contrast, it found that only 11 percent of people found that the amount of federal taxes they themselves paid was what bothered them the most, with 28 percent naming the complexity of the tax system.

Possibly the greatest dissatisfaction with the tax system is not with taxes per se, but the widespread feeling that the money is simply wasted. The American Enterprise Institute compendium shows that the percentage of people who believe that the government wastes a lot of their money has risen over time. Recent polls put the percentage in the 70 percent to 80 percent range, almost twice what it was in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

When asked what percentage of all federal spending is wasted, a variety of polls routinely put the figure around half. People also believe that wasteful spending has risen over time and that they themselves get little if any value from the taxes they pay. Overwhelmingly, people say that how their taxes are spent bothers them more than the amount they pay.

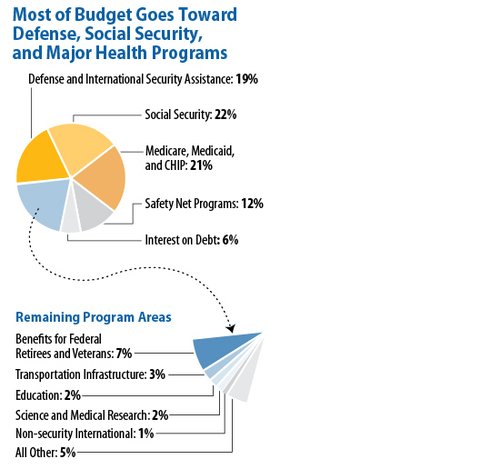

Not surprisingly, people prefer the idea of paying less in taxes and getting less from government over the idea of paying more in taxes and getting more services from government. It’s hard to see how this could be otherwise given the distribution of federal spending. As the chart below from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows, the vast bulk of it goes to national military programs that no one actually sees, programs for the elderly and poor, or interest on the debt. Programs that average people might see in their own lives, such as education or transportation, are a tiny fraction of spending. Even over a lifetime, most people expect to get back less from government than they pay in taxes.

2012 Figures from the Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2014 Historical Tables, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

2012 Figures from the Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2014 Historical Tables, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

In terms of tax reform, people remain sympathetic to the idea of a flat tax despite their general sympathy for progressivity and the idea that government should actively narrow the distribution of income.

Almost everyone thinks the federal tax system is too complicated and in need of major overhaul. In principle, people are willing to give up deductions in return for lower rates, but when questioned about specific deductions they usually support the big ones. An April 2011 Gallup poll found 60 percent to 70 percent of people opposing elimination of the home mortgage deduction, the deduction for state and local taxes or the deduction for charitable contributions, either to reduce the deficit or in return for lower tax rates.

Politically, Republicans and those with high incomes tend to hate taxes and doing their taxes more than Democrats and those with low incomes. According to a new Pew poll, 60 percent of Republicans say they hate doing their taxes compared with 46 percent of Democrats; 63 percent of those with incomes over $75,000 hate doing their taxes compared with 50 percent of those with incomes below $30,000.

It’s undoubtedly the case that one’s decision to identify with the Republicans or Democrats in the first place has a lot to do with taxes.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/16/what-people-think-about-taxes/?partner=rss&emc=rss