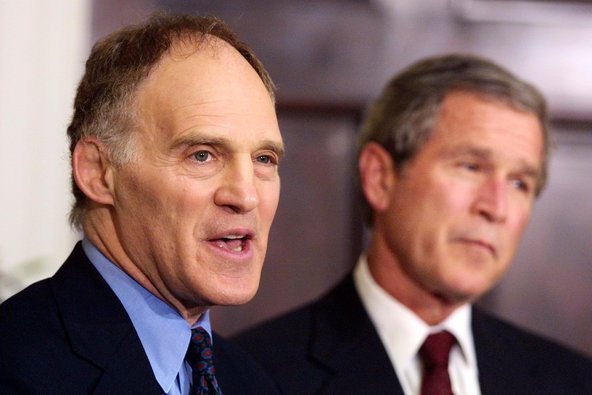

Manny Ceneta/Agence France-PresseStephen Friedman, President Bush’s former economic adviser, is one of the top earners on Goldman’s board, making $503,287 in 2011.

Manny Ceneta/Agence France-PresseStephen Friedman, President Bush’s former economic adviser, is one of the top earners on Goldman’s board, making $503,287 in 2011.

Wall Street pay, while lucrative, isn’t what it used to be — unless you are a board member.

Since the financial crisis, compensation for the directors of the nation’s biggest banks has continued to rise even as the banks themselves, facing difficult markets and regulatory pressures, are reining in bonuses and pay.

Take Goldman Sachs, where the average annual compensation for a director — essentially a part-time job — was $488,709 in 2011, the last year for which data is available, up more than 50 percent from 2008, according to Equilar, a compensation data firm. Some of the firm’s 13 directors make more than $500,000 because they have extra responsibilities.

And those numbers are likely to skyrocket for 2012 because the firm’s shares rose more than 35 percent last year and its directors are paid in stock. Goldman Sachs is expected to release fresh pay data in the coming weeks.

Goldman’s board is the best compensated of any big American bank and the fifth-highest paid of any company in the country, according to Equilar. Some of its rivals are not that far behind. The nation’s biggest banks paid their directors over $95,000 a year more on average in 2011 than what other large corporations paid.

Goldman defends the board’s pay, saying that the bulk of the compensation is in stock that directors cannot touch until after they have left the board.

That arrangement, the firm says, aligns directors’ interests with those of shareholders.

“The board’s pay is set at a level that reflects the firm’s long-term performance as well as directors’ substantial time commitment and the increased demands placed on them in recent years by new laws and regulations,” said David Wells, a Goldman spokesman.

More broadly, banks and compensation experts say, financial firms must now pay a premium to entice and keep qualified directors.

After the financial crisis, some financial firms’ boards were criticized for being asleep at the wheel and not understanding the risks being taken. Recruiters say banks are redoubling efforts to recruit directors with more financial expertise who can exercise better oversight.

Yet it is also a balancing act, because too much pay may end up giving boards an incentive to not rock the boat.

Some Wall Street insiders also question the need to pay bank directors more than their counterparts at other big corporations, arguing that the increased regulation has actually limited bank boards’ ability to perform important tasks, like raising capital and issuing dividends. Even when it comes to paying senior executives, boards have less leeway because regulators have pressured boards to bring down executive pay.

“About the only thing bank directors have more of these days is meetings,” joked one senior Wall Street executive who has frequent interaction with his board but spoke on the condition he not be named because he was not authorized to speak on the record.

“Regulators have all but stripped boards of the main powers they had before the crisis.”

After Goldman, Morgan Stanley’s director pay is the second highest on Wall Street, with an average of $351,080, roughly the same as it was in 2008 but much higher than the pay at bigger and more complicated rivals like JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup.

Board pay at Morgan Stanley has drawn criticism from Daniel S. Loeb’s hedge fund, Third Point, which recently bought 7.8 million shares, or a 0.4 percent stake, in the firm. While praising Morgan Stanley and its management, Mr. Loeb said in a letter to investors how “surprised” he was about how much its directors received.

“We hope Morgan Stanley will show that its reinvention begins at the top and set an example for the company by quickly revising its board practices,” he wrote.

At Citigroup, directors make an average of $315,000 a year, according to Equilar, up 64 percent from 2008. The value of the annual cash retainer and deferred stock award Citigroup directors receive has not changed since 2005, but the pay for additional work, like leading a committee, has risen.

Of the five financial institutions to have reported director pay for 2012, JPMorgan is the biggest, but it gives its directors compensation, on average, worth $278,194 each. Only Bank of America, where directors are paid $275,000 each, pays less.

All told, the average compensation for a director at one of the six biggest banks in 2011 was $328,655, according to Equilar. This compares with $232,142 at almost 500 publicly traded companies analyzed in a study by the executive search firm Spencer Stuart. In 2012, that number rose to $242,385.

“I get you have to pay up for sophisticated board, but what is that complexity worth?” said Timothy M. Ghriskey, co-founder of the Solaris Group, a financial services shareholder that voted in 2011 to reject a pay plan for top executives at Citigroup. “Does it take $200,000 or $500,000? The discrepancy between a board like JPMorgan and Goldman is confusing.”

This spring, the big banks will hold shareholder meetings. While executive pay is often a hot-button issue, Mr. Ghriskey said it was unlikely that there would be a shareholder revolt on board pay this year, in part because the numbers aren’t that big on an individual basis.

Still, Lynn Joy, a senior adviser with the executive pay consulting firm Exequity, said board pay deserved more attention, especially at financial firms, which are looking to cut costs.

Shareholders, she said, should look at the total cost of operating a board. In the case of Goldman, its 11 independent directors make roughly $5 million, and the cost of holding board meetings, sometimes overseas, can run many millions more. “It adds up,” she said.

Shareholders vote on directors, but a board almost always sets director pay packages, in consultation with compensation experts.

For any director, the work comes in fits and starts. Bank boards met more frequently during the financial crisis to plot strategy, and Citigroup’s directors put in extra time last year in their discussions over whether to replace Vikram S. Pandit, the bank’s chief executive.

While board pay has increased at every major bank, the rise is most pronounced at Goldman, in part because directors’ compensation is driven by the value of the firm’s stock, which closed on Thursday at $147.15.

While compensation for Goldman directors is up substantially from 2008, it is actually down from 2007, when the stock price was higher and directors were paid an average of $670,292 each, according to Equilar.

In 2011, Goldman directors were each granted 2,500 shares, with a value of more than $250,000. This is on top of an annual retainer of stock valued at $75,000. A director who is a chairman of a board committee is paid more.

Goldman’s directors met 15 times in 2011, and there were more meetings that involved only the firm’s independent directors.

Stephen Friedman and James A. Johnson are the top earners on Goldman’s board, each making $503,287 for their service that year, according to Equilar.

In 2009, during the height of the financial crisis, Goldman directors decided to take no compensation for their service.

Other banks pay some cash and grant stock up to a certain dollar amount, limiting the value. At JPMorgan, for example, directors are compensated for extra duties, but the value of their main share grant cannot exceed $170,000.

In a regulatory filing explaining the pay of its board, Goldman noted that directors could not sell the stock grants until they left the board, and even then there was a waiting period. The firm also said independent directors did not get paid to attend meetings, a practice on some other boards.

“While the Goldman pay is high, the directors are paid all in equity that cannot be cashed until they leave the board,” added Lucian A. Bebchuk, a professor at Harvard Law School. “These features are beneficial for shareholders but reduce the value of the compensation for the directors.”

Investment Bank Director Pay

A version of this article appeared in print on 04/01/2013, on page A1 of the NewYork edition with the headline: Pay for Boards At Banks Soars Amid Cutbacks.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/03/31/pay-for-boards-at-banks-soars-amid-cutbacks/?partner=rss&emc=rss