Laura D’Andrea Tyson is a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and served as chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Clinton.

In a surprising year-end act of bipartisanship, Representative Paul D. Ryan, Republican of Wisconsin, and Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon, offered a proposal to reduce the growth of Medicare spending, envisioning a fundamental transformation of Medicare to a “managed competition” or “premium support” system.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

In their plan, the government would provide a subsidy to Medicare beneficiaries to choose among competing insurance plans, including the traditional fee-for-service Medicare program.

Mr. Ryan and Mr. Wyden say their system would control the growth of Medicare spending better than the current system by encouraging more efficient cost-sensitive decision-making by both providers and consumers. This incentive argument has considerable analytical appeal, especially among economists – competition usually reduces costs in most markets.

But the markets for insurance and health services are not like most markets, and there is scant evidence to support the Ryan-Wyden assertion, as Uwe E. Reinhardt noted in Economix last week. The cost savings from managed competition are hypothetical and uncertain – in fact, there are reasons to fear that such a system could actually increase costs.

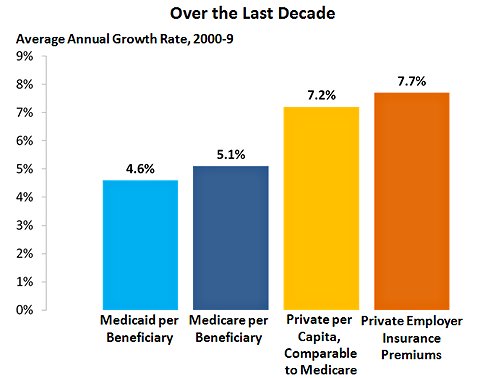

Despite competition and choice in the private insurance system, Medicare spending has grown more slowly than private insurance premiums for comparable coverage for more than 30 years.

From 1970 to 2009, Medicare spending per beneficiary grew by an average of 1 percentage point less each year than comparable private insurance premiums. Between 2000 and 2009, Medicare’s cost advantage was even larger – its spending per beneficiary grew at an average annual rate of 5.1 percent while per-capita premiums for private health insurance plans grew at 7.2 percent, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

In inflation-adjusted terms, Medicare spending per beneficiary increased more than 400 percent between 1969 and 2009 while private insurance premiums increased by more than 700 percent.

What explains Medicare’s sustained cost advantage over private insurance? Medicare has much lower administrative costs than private insurance (administrative costs account for about 14 percent of health care spending, or a whopping $360 billion a year).

And Medicare has considerable negotiating leverage with providers as a result of its huge enrollment. Private insurance plans are unable to negotiate payment rates with providers that are as low as Medicare’s rates, even though Medicare’s negotiating authority is tightly limited and often undermined by Congress.

Advocates of premium support point to the Federal Employees Health Insurance plan as an example of how competition would work in Medicare. But this plan has been no more successful than private-employer-provided insurance at controlling the growth of insurance premiums.

And traditional fee-for-service Medicare outperforms both, even though its elderly beneficiaries include a sizable share of the sickest individuals who are the largest consumers of expensive health-care services.

In the Ryan-Wyden version of premium support, the fee-for-service Medicare would compete with private insurance plans that offer a standard package of defined Medicare benefits or an actuarially equivalent one.

All participating plans would take part in an annual competitive bidding process, and the bid by the second-least expensive private plan or by traditional fee-for-service Medicare, whichever is lower, would set the benchmark for the federal subsidy granted to Medicare beneficiaries to purchase the plan of their choice.

A beneficiary who chooses a more expensive plan than the subsidy for which he or she was eligible would have to pay the difference; a beneficiary who chooses a less expensive plan would receive a rebate.

The Ryan-Wyden plan links the size of the Medicare subsidy to systemwide health care costs through the competitive bidding process and assumes that competition will slow the future growth of these costs.

But in an explicit acknowledgment that the resulting cost savings are speculative, the plan also contains a backup cap that would limit the growth of federal spending on Medicare per beneficiary to the rate of growth of nominal gross domestic product plus 1 percentage point. Historically, both private health-care costs and Medicare spending per capita have increased at faster rates.

The Ryan-Wyden proposal is ambiguous about what would happen if the cap became binding. The proposal says Congress “would be required” to intervene and “could” implement policies to change provider payments and premiums for beneficiaries.

Congressional intervention to control provider payments would shift the burden of higher-than-anticipated costs to providers from the federal government and would effectively signal the end of managed competition as the mechanism to control costs.

In lieu of such intervention, Mr. Ryan has indicated that the cap would apply to the growth of the subsidy itself, and this would shift the burden of higher-than-anticipated costs to beneficiaries from the federal government.

That would mean that the Ryan-Wyden system would devolve from a premium-support system in which the growth of the subsidy depended on actual health-care costs to a voucher system in which it was delinked from such costs.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 sets the same target for the future growth of Medicare spending. But unlike the Ryan-Wyden proposal, the act does not undercut Medicare’s ability to control costs by weakening the negotiating influence derived from its national enrollment.

Instead, the act puts Medicare at the center of reforms to create accountable care organizations, reduce payments to hospitals with high admission rates, bundle payments to providers and carry out comparative effectiveness research. Such reforms are essential to controlling costs and improving care.

And only Medicare has the clout and responsibility to accomplish them.

Despite competition, private insurers have been unwilling or unable to spearhead such changes, opting instead to pass rising costs onto consumers through higher premiums and to rely on Medicare to foster efficiency-enhancing systemwide reforms.

That’s why the Congressional Budget Office has consistently refused to recognize large potential savings in health care costs from reforms to increase competition among private insurance plans. Indeed, the C.B.O. has concluded that replacing traditional Medicare with competition among such plans would drive up total health care spending per Medicare beneficiary.

The Affordable Care Act also creates an Independent Payment Advisory Board, composed of nonpartisan health-care experts responsible for producing proposals to keep Medicare spending within the target while shielding beneficiaries; increases in premiums and cost-sharing are precluded. These proposals would take effect automatically unless the president and Congress acted to overturn them.

In 1998, a National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare, chaired by Senator John Breaux, Democrat of Louisiana, and Representative Bill Thomas, Republican of Maryland, developed a premium-support proposal similar to Ryan-Wyden but without an enforceable backup cap on spending. The commission failed to achieve the supermajority required for a formal recommendation to Congress.

I was a commission member appointed by President Clinton, and at the time I thought premium support was worth trying. Ultimately, however, I could not recommend the commission’s proposal because it rested on unrealistic assumptions about the magnitude of the cost savings that would result from competition. I believed competition might ease Medicare’s future financing gap but would not eliminate it, and I was concerned that the commission offered no credible cost-containment measures to address this gap.

I have similar reservations about the Ryan-Wyden plan. No evidence supports the plan’s assumption that a premium-support system with competitive bidding would control Medicare spending more effectively than traditional Medicare.

Nor does the plan contain enforceable cost-containment measures like those in the Affordable Care Act. And the plan’s backup cap on the growth of Medicare delinked from the actual growth of health care costs could shift the burden onto Medicare beneficiaries in the form of higher premiums and reduced access and quality of care.

This post has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: December 30, 2011

An earlier version of this post misstated the year in which the Affordable Care Act was signed into law. It was 2010, not 2011.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=0fada29c5e545ce8743720df26f66d0b