Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

Traditionally, the theory driving discussions on the high cost of health care in the United States has been that there is enormous waste in the system, taking the form of excess utilization of care. From that theory it follows that methods of controlling the growth of health spending should focus on ways to reduce the use of unnecessary or only marginally beneficial health care.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Largely overlooked in these discussions has been the elephant in the room: the extraordinarily high prices Americans pay for health care. However, as a group of us noted in a paper in 2004, “It’s the Prices, Stupid,” it is higher health spending coupled with lower – not higher — use of health services that adds up to much higher prices in the United States than in any other member nation of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Aside from a few high-tech services, Americans actually use less health care and rely on fewer real health-care resources than do residents of other industrialized countries.

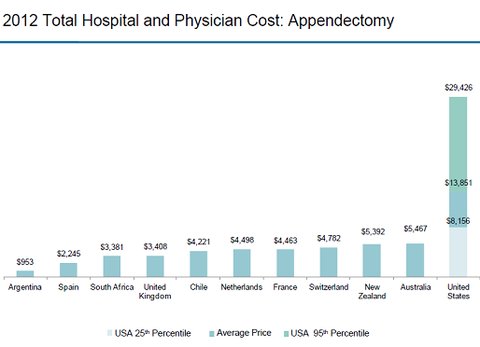

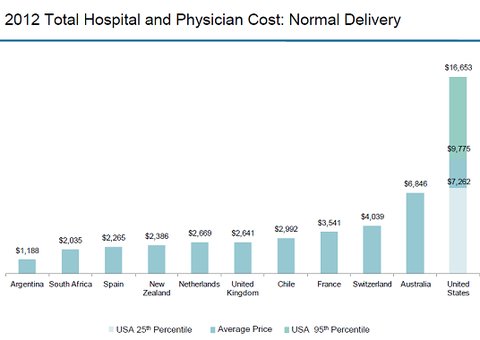

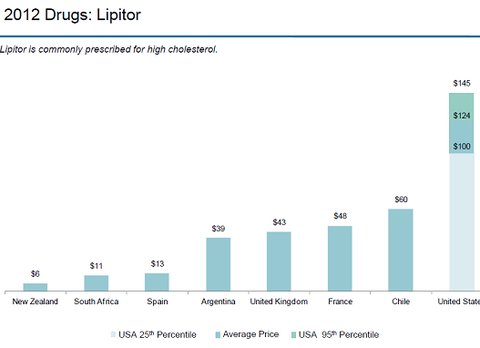

Readers who want to get a peek at this elephant in the room should peruse the set of slides published a few days ago by the International Federation of Health Plans, a global network of private health-insurance plans with 100 members in 31 countries. The federation annually surveys prices actually paid for selected health care goods and services in the different countries.

Shown below are three slides from the set:

International Federation of Health Plans

International Federation of Health Plans

International Federation of Health Plans

International Federation of Health Plans

International Federation of Health Plans

International Federation of Health Plans

In most other countries, prices for health care goods and services are not negotiated between individual health insurers and individual physicians, hospitals or drug companies, as they are in the private insurance sector in United States.

Instead prices there either are set by government or negotiated between associations of insurers and providers of care, on a regional, state or national basis. The single prices for other countries shown in the chart therefore can be taken representative of prices actually paid there.

By contrast, as can be seen in the charts, in the United States there is quite a range of prices for the identical good or service.

Ideally, the federation should also have shown the median for prices in the United States. The median represents the midpoint of a frequency distribution; if the distribution of prices is skewed toward either low or high values, the average will be either above or below the midpoint and may not be representative.

Whatever the case may be with the distributions of American prices underlying the charts, it seems clear that the prices for health care in the United States are much higher than they are in other nations. As we noted in the paper cited above, it goes a long way toward explaining why, on average and in purchasing-power parity dollars per-capita, health spending in the United States is so much higher than it is elsewhere in the world.

My explanation for the relative high prices Americans pay for health care relative to other countries is that the payment side of the health care market in the private sector is fragmented, weakening the bargaining power of individual insurers, especially vis-à-vis the increasingly consolidated hospital sector, although other factors, including malpractice premiums, play a part as well.

To endow the payment side of health care with more market muscle, I have proposed an all-payer system based on the models used in Germany or Switzerland or in the state of Maryland. In these systems, government does not dictate prices. Instead, health care prices are negotiated at what Europeans call a “quasi market” level.

Average or median prices aside, however, the federation charts also show that the variation of prices for identical items within the United States – even within a single city – dwarfs the cross-national variation in prices for the same item. That phenomenon has begun to attract attention in the news media only lately.

As Consumer Reports noted in an illuminating article, “Health care prices are all over the map, even within your plan’s network.” The chart at the bottom of the article, based on the Healthcare Blue Book on prices, is especially revealing.

The high variance of health care prices in the United States can be explained in good part by the opacity of these prices. Both government and the private sector have done their best to maintain that opacity.

It is possible to find prices paid by Medicare on the Web, but they are written in code that means something to the providers of health care although little to patients.

Pretend to be a prospective patient searching the Web for Medicare fees. Google “Medicare fee schedules.” At the top of the list you will find this Web site. Try to find the fee for a screening colonoscopy in your area.

If you get frustrated, try this one.

Good luck on your hunt for Medicare fees.

Fees in the private health care sector have been jealously guarded trade secrets among insurers and providers of health care. True, some health insurers now provide their insured members with “cost estimates,” by provider and by major procedure, of what the procedures rendered by a particular providers might cost patients out of pocket, but not full prices. I have found the site for that purpose on my insurance policy very difficult and cumbersome to navigate.

For uninsured patients (also known as self-pay patients) full price information is hard to come by. I tried it again just the other day, calling up a New Jersey hospital and seeking a price for a colonoscopy. After a runaround of several telephone calls, I gave up. I have described the attempt more fully in response to a comment on the previous blog post.

It is truly remarkable that few state governments have made any effort to provide their residents with greater price transparency in health care, as well they could and should.

A report on March 18, “Report Card on State Price Transparency Laws” by the Catalyst for Payment Reform and the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute gives 29 states the failing grade of F on this score, including New York and New Jersey. Another 6 earned a D, barely passing. Only Massachusetts and New Hampshire earned an A.

With so much carefully guarded and government-shielded opacity on health care prices, it should be no surprise that prices for health care vary as much as they do in the United States, even within small regions and for the same health insurer.

It will not change until citizens make it an issue in political campaigns.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/29/u-s-health-care-prices-are-the-elephant-in-the-room/?partner=rss&emc=rss