Laura D’Andrea Tyson is a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and served as chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Clinton.

In late 2008, the United States economy was caught in the midst of what proved to be its longest and deepest recession since the end of World War II. Frightened by steep and self-reinforcing declines in output and employment, both the Federal Reserve and the federal government responded quickly and boldly. The Federal Reserve dropped the federal funds rate to near zero, where it remains today, and began its controversial “quantitative easing” purchases of long-term government securities to contain long-term interest rates.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Fueled by the 2009 federal stimulus package, discretionary fiscal policy was also expansionary in 2009-10, adding to growth during the first year of the recovery at roughly the same pace that fiscal policy had achieved during previous recoveries.

Then, in a sharp break with history, fiscal policy became a drag on growth in the second year of recovery, and since then the drag has intensified. What explains the premature and counterproductive turn toward fiscal austerity despite the high unemployment rate and the large gap between actual and potential output?

Before the Great Recession, there was a near consensus among economists that monetary policy alone could stabilize aggregate demand and keep the economy on its potential growth path. Under normal economic conditions, countercyclical fiscal policy was thought to be unnecessary. It was also thought to be both ill timed, because of lags in Congressional decision-making, and wasteful, because choices among fiscal measures were driven by politics and rent-seeking rather than cost-benefit considerations.

Most economists also believed that changes in discretionary fiscal policy would have small effects on aggregate demand and output — that the multipliers for such changes were small — and this belief was supported by empirical research based on “normal economic conditions.”

But the conditions confronting fiscal policy in late 2008 were anything but normal. Output, employment and stock values were falling at a faster pace than before the Great Depression, and short-term interest rates had fallen to their zero lower bound. At least in the short term, conventional monetary policy alone could not stabilize the economy, so over dire warnings from some macroeconomists, in early 2009 Congress answered President Obama’s request for a large temporary stimulus package to end in 2011, by which time it was hoped or expected that a strong recovery would be under way.

Subsequent empirical analysis indicates that the stimulus worked. New research confirms that the multipliers for fiscal policy are significantly larger during downturns when there is considerable excess capacity and when interest rates are at or near their lower bound. They are also larger when private actors are credit-constrained, so their spending depends more on current income than on future expected income. These were the conditions in 2010-11. Even using a range of lower multiplier estimates consistent with more normal conditions, the Congressional Budget Office found that the effects of the stimulus on output and employment were in the predicted range.

But the depth of the recession and the sluggishness of the recovery had been underestimated. Foreclosures and excess housing inventory constrained residential investment, and high unemployment, falling wages and deleveraging constrained household consumption. In 2011, as the stimulus came to an end, private spending was recovering but at an anemic and fitful pace.

And two years of short-term interest rates near zero and quantitative easing had exposed the limits of conventional monetary policy and raised anxieties about the risks of unconventional monetary policy.

There was a strong case for additional fiscal stimulus in 2011, and that is what President Obama proposed. But this time Congress rebuffed most of his recommendations, and since then fiscal policy has shifted to even more contraction in the form of strict caps on discretionary federal spending, increases in taxes and the sequester. According to the International Monetary Fund, fiscal policy will reduce gross domestic product in the United States by 1.8 percent this year.

Since 2011, proponents of fiscal austerity have repeatedly raised concerns that the large increases in the government deficit caused by both the recession itself and discretionary fiscal stimulus would lead to a spike in long-term interest rates. Bill Gross, the bond-market savant and influential chief executive of Pimco, warned that a spike would occur by the late summer of 2011. The downgrading of United States government debt in August 2011 after the Congressional showdown over the debt limit amplified these concerns.

But long-term interest rates did not spike; instead, they fell to historic lows in 2012 and are currently less than 2 percent, despite further increases in government debt. The experience of the last four years demonstrates that there is no simple predictable relationship between the government deficit and long-term interest rates. The relationship depends on economic conditions. Under current conditions, as long as the recovery remains weak, with considerable slack between actual and potential output, subdued inflationary expectations and highly accommodative monetary policy, long-term interest rates are likely to remain low.

As Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, noted in a recent speech, the behavior of long-term interest rates during the last several years has few precedents, but it is not puzzling: it follows from the weakness of the recovery and the implications for monetary policy.

In an effort to avoid the kind of surprise that rocked the bond market in 1994 when the Federal Reserve suddenly and significantly increased short-term rates, driving long-term interest rates sharply higher and imposing sizable losses on bond holders, the Federal Reserve has been transparent about its strategy: as long as current and expected inflation remains near 2 percent, the Fed will keep short-term interest rates where they are until the unemployment rate falls to around 6.5 percent.

When not fixated on bond-market anxieties, proponents of fiscal austerity have focused on variants of the “crowding out” argument that a high and rising government debt crowds out private investment and reduces economic growth. But this argument does not apply under current conditions, when there is significant excess capacity and when the private sector is running a financial surplus, with saving to spare to cover the government’s borrowing requirements.

But what about evidence of a possible negative relationship between the ratio of public debt to G.D.P. and economic growth – evidence that burst into fiscal debates in 2010 with the publication of the paper by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff purporting to show that over the long term, growth declines sharply when public debt tops 90 percent or more of G.D.P.?

As the authors themselves acknowledge, the relationship between public debt and growth is one of correlation, not causality. Over time, slow growth is as much a cause of high public debt as high public debt is a cause of slow growth.

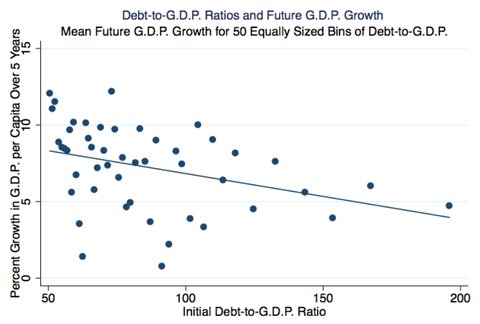

In our recent paper for the International Monetary Fund, Brad DeLong and I (with assistance from Owen Zidar) find a negative relationship between public debt burden and growth, but the effects are modest: raising the public debt-to-G.D.P. ratio from 50 percent to 150 percent for five years is associated with a growth reduction on the order of 0.6 percentage points per year over the next five years, and controlling for country and decade effects reduces the negative effect on growth by more than half.

This chart shows results for debt-to-G.D.P. above 50. Debt-to-G.D.P. above 200 is set to 200.

This chart shows results for debt-to-G.D.P. above 50. Debt-to-G.D.P. above 200 is set to 200.

Like others, we also find that there is no threshold debt ratio beyond which growth drops precipitously. Despite the warnings of fiscal austerians, Mr. Bernanke is right: “Neither experience nor economic theory clearly indicates the threshold at which government debt begins to endanger prosperity and economic stability.”

In recent months, the lessons learned about fiscal policy over the last several years have begun to shift the policy debate. In its latest World Economic Outlook, the I.M.F. raised alarms about excessive and counterproductive fiscal austerity in the United States, Britain and Germany.

A growing number of European political and business leaders are warning that harsh fiscal contraction is consigning Europe to prolonged stagnation or worse. Even Mr. Gross is now asserting that bond markets do not want severe belt-tightening and that austerity is not the way to promote growth.

Unfortunately, Congress is not listening. As William C. Dudley, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, observed in a recent speech, the United States has the opposite of the fiscal policy we need: too much fiscal contraction in a still-vulnerable economy now, without a credible plan to reduce the federal budget deficit in the long run.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/03/lessons-on-fiscal-policy-since-the-recession/?partner=rss&emc=rss