Courtesy HSH.com

Courtesy HSH.com

Anyone who has ever bought a home knows how confusing it can be to decide on the best financing options. Is it better to pay closing costs upfront or build them into the cost of the loan and pay them over time?

It’s important to be able to compare options, now that the housing market is recovering and people are willing to start buying again. Home prices saw another broad-based increase in March, according to the latest statistics from Standard Poor’s Case-Shiller home price index.

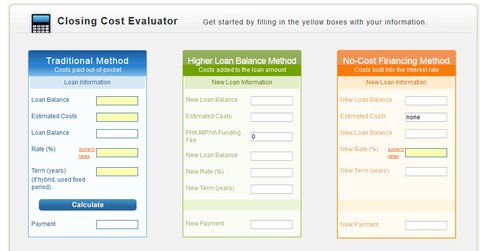

To help potential home buyers weigh the options, and see how much they will cost over time, the real-estate site HSH.com has created the “FeePay BestWay” closing-cost calculator.

Keith Gumbinger, HSH.com’s vice president, designed the calculator after helping his son walk through various scenarios while applying for a mortgage.

The calculator lets you plug in the amount of the mortgage, then automatically factors in two points, which is lender lingo for 2 percent of the loan amount, for fees. (The fees include those for an appraisal of the property, your credit report, a home inspection, discount points, title search.) You can change the amount of the fees, if you expect your costs to be greater or less.

The calculator then shows you three options for paying the closing costs (although all three options might not be available to you, depending on your specific circumstances).

The “traditional” option assumes that you pay the costs up front. This generally gets you the lowest interest rate, but you will be out of pocket for the cash.

The “higher loan balance” option assumes that you add the costs to the loan principal, which means you not only pay the fees, but you’ll pay interest on them. However, this might be beneficial if it allows you to use the extra cash you would have used for fees to make a bigger down payment. That can possibly help you avoid having to pay mortgage insurance. Or, you may wish to hold on to some cash for emergency purposes.

The third option is the “no cost” option — perhaps a misnomer as it means you are trading the lack of cash for the fees for a somewhat higher interest rate. This option could be beneficial, however, if you don’t plan to stay in the home for life of the loan.

Each option then shows a chart, showing how the interest payments and loan balances change over the life of the loan.

If you were to suddenly have to sell your home after a year, the “no cost” option could actually be less expensive because you haven’t paid as much out of pocket. But in general, over time, the traditional or “built in” options cost you less.

Take a look at the calculator and let us know if you find it helpful.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/a-calculator-to-compare-closing-cost-options/?partner=rss&emc=rss