Courtesy Chubb Personal Insurance

Courtesy Chubb Personal Insurance

Hurricane season began on Saturday, and the federal government is predicting an “active or extremely active” year. So if you live in a hurricane-prone area, now is a good time to inspect trees near your home for possible weakness that could lead to damage during a storm with strong winds.

Most standard homeowners’ policies cover damage from branches and trees that fall on your home or garage during a wind or ice storm; they also cover removal of the tree, at a cost of $500 to $1,000, depending on the policy. (If the tree falls on your property but doesn’t damage anything, there’s usually no coverage for its removal.)

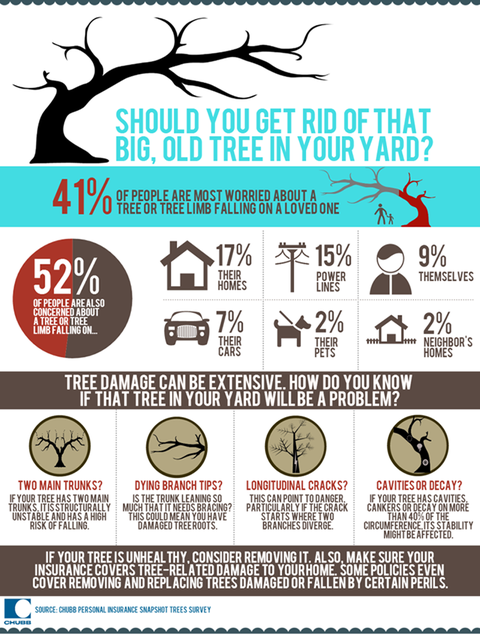

But a more worrisome risk is that the tree or branch will injure you or a family member when it falls. In a recent survey by Chubb Personal Insurance about damage from a falling tree or branch, more than 41 percent of those surveyed said they most worried about the tree falling on a loved one. (The telephone survey of 1,004 people was conducted in March by ORC International).

Scott Spencer, worldwide appraisal and loss prevention manager with Chubb, said in a phone interview that homeowners should periodically assess the health of trees near their homes. Often, homeowners assume that because a tree has weathered previous storms, that it must strong. But exposure to storms may weaken trees in some cases, so they need to be reassessed.

Of greatest concern are trees within the “fall zone,” he said — trees that would hit your house if they fell down. Trees with forked trunks — that is, they appear to have two main trunks — are unstable and are at greater risk of falling, he said.

Signs that trees may be in poor health include branches with dead tips; cankers or rot on large portions of the trunk; or mounds or divots near roots, that may indicate rotting. Trees near areas that recently have been under construction should be carefully checked, since excavation equipment can damage roots.

If you have doubts about a tree’s health, it’s wise to consult a professional arborist. “You need to consult a tree expert, not just a neighbor with a chainsaw,” he said, because improper pruning may cause more problems than it solves by making the tree unstable.

The International Society of Arboriculture certifies arborists and has a search tool in its Web site to help you find a professional near you. The site also lists additional ways to check on a tree’s health.

If the tree is in poor health and is positioned so that it could fall on your home, you may want to consider having it removed. Generally, though, you’ll pay out of pocket for this; insurance policies cover damage from falling trees, but not prevention.

And as for the fear that a tree or limb might fall on you or a family member, Jeanne Salvatore, a spokeswoman for the Insurance Information Institute, said the resulting medical costs would be covered not by your homeowner’s policy, but by your medical insurance. (If, however, the tree or limb injured someone else, like a guest or a pizza delivery boy, and you were sued, the liability coverage of your policy would cover your losses up to the limits of your policy, she said. Mr. Spencer of Chubb said there would typically need to be a finding that the homeowner was negligent in maintaining the tree.)

How do you maintain trees near your home? Have you ever had one fall on your house?

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/checking-trees-as-hurricane-season-starts/?partner=rss&emc=rss