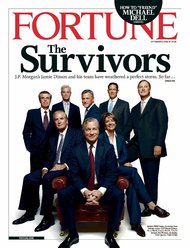

Clockwise from top left: James Staley, William Winters, Heidi Miller, Steven Black, Charles Scharf, Barry Zubrow, William Daley, Jay Mandelbaum, Frank Bisignano and Ina Drew.

Clockwise from top left: James Staley, William Winters, Heidi Miller, Steven Black, Charles Scharf, Barry Zubrow, William Daley, Jay Mandelbaum, Frank Bisignano and Ina Drew.

10:35 a.m. | Updated

In the depths of the financial crisis, Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan, and his top lieutenants were hailed as “The Survivors” on a Fortune magazine cover. Today, of the 15 executives featured in that article, only three remain — and one of them has been demoted.

The most recent high-level exit at the bank — that of the co-chief operating officer, Frank J. Bisignano, regarded within JPMorgan as something of an operational wizard — has heightened worries about the persistent executive turnover at the bank and raised fresh questions about who is ready to succeed Mr. Dimon one day.

Revolving Door

View all posts

For Mr. Dimon, who is 57, the latest departure comes at a precarious time, just weeks before the results are tallied on a shareholder vote on whether to split the roles of chairman and chief executive. Mr. Dimon currently holds both jobs. With voting now under way, the bank had hoped to keep a low profile, according to people briefed on the matter but not authorized to speak on the record.

In the last four years, Mr. Dimon’s inner circle has been winnowed by the departures of William Winters, Heidi Miller, Steven Black, Charles Scharf, William Daley and Jay Mandelbaum.

And while people close to the chief executive say he is not worried about the executive turnover, others wonder if the many reshufflings at the top point to a larger problem within the bank.

More changes in the executive suites could distract shareholders from the bank’s successes. Earlier this month, JPMorgan reported its 12th consecutive quarterly profit, bolstered by strong revenue from investment banking and mortgage-related businesses. JPMorgan executives are emphasizing the positives of the bank’s businesses in making their case to shareholders.

JPMorgan’s Trading Loss

Of the 15 leaders at JPMorgan profiled in a September 2008 article for Fortune magazine, only three remain with the bank.

Of the 15 leaders at JPMorgan profiled in a September 2008 article for Fortune magazine, only three remain with the bank.

Still, the turnover at the top is a reminder of unfinished business at JPMorgan as the bank wrestles with the fallout from a multibillion-dollar trading loss in 2012. A number of agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, are investigating the trading losses. The inquiries and the need to improve relations with regulators promise to be a burden for those executives staying on.

The losses, which stemmed from a soured bet on credit derivatives, prompted a number of the recent departures.

Shortly after the losses were announced in May 2012, Ina R. Drew, who headed the unit at the center of the trades, resigned. In January, JPMorgan produced a 129-page internal report that dissected the bad bet and offered a rare window into the factors that led to the risk breakdowns. Losses on the trades have swelled to more than $6 billion.

The trading missteps also ensnared Barry L. Zubrow, who was a chief risk officer at the bank during the time that the chief investment office was making riskier bets. He announced his departure from the bank in October.

The trading debacle, however, explains only part of the executive exodus. In January, James E. Staley, who was the former head of JPMorgan’s investment bank, announced he would leave to join a hedge fund.

Another executive, S. Todd Maclin, ceded his spot on JPMorgan’s management committee and moved to Texas, where he is chairman of the consumer and commercial bank. Within the bank, some executives disagree that Mr. Maclin was demoted, noting that the move to Texas was prompted by the executive. Before the transition, they say, Mr. Maclin groomed a successor and has since agreed to help the bank bolster its Texas business.

Mr. Dimon has struck a positive tone about the turnover, writing in his annual letter to shareholders that the changes are “not as pronounced” as they may appear. He added that the exits did not leave a leadership vacuum, in part because the vacancies were being filled by people who already had experience in the roles they were stepping into.

For example, Matthew E. Zames, who now becomes the bank’s sole chief operating officer, already shared the job with Mr. Bisignano.

Mr. Bisignano, whose departure was announced on Sunday, is leaving JPMorgan to become chief executive of First Data, a payment-processing firm. His is a particularly difficult loss for the bank, according to people briefed on the matter, because he was widely considered to be skilled at tackling thorny problems at a time when the bank has been faulted over weak oversight in places.

The most recent departures put a spotlight on a handful of possible successors to Mr. Dimon, including Mr. Zames. Mr. Dimon lauded Mr. Zames in a statement on Sunday, calling him a “proven business executive” who will “continue to have an important impact on our company.” Mr. Zames joined JPMorgan in 2004 from Credit Suisse.

Another potential executive to succeed Mr. Dimon is Michael J. Cavanagh, who held the chief financial officer post from 2004 to 2010. As part of the management overhaul in the wake of the trading losses, Mr. Cavanagh, like Mr. Zames, gained more power within the bank. He became the co-chief executive of the corporate and investment bank.

Mr. Cavanagh has a long history with JPMorgan’s chief executive. He was head of strategy and planning at Bank One, where he worked closely with Mr. Dimon.

Mr. Dimon appears unfazed by the steady stream of departures. At meetings inside the bank he has lauded the executive team that remains, and although the bank’s succession plans are not known, he has told people close to him that he is confident the bank will be in good hands when he does decide to leave.

JPMorgan shareholders are scheduled to meet on May 21. At that time the company will announce the results of a shareholder proposal calling for the separation of the roles of chairman and chief executive officer.

In recent years, pension funds and other shareholders have pushed companies to split these roles. Wall Street executives have largely scoffed at the idea, saying a powerful lead director is just as effective as a nonexecutive chairman. Goldman Sachs recently reached an agreement with a shareholder group to withdraw a resolution to split its chairman and chief executive jobs.

Such a vote is still advancing at JPMorgan, however, and last year a similar proposal was supported by 40 percent of the shares voted. Last year’s vote happened not long after JPMorgan first disclosed the trading losses to its investors, and in recent interviews, many shareholders said the news was so fresh at the time that it did not play a factor in how they voted.

The trading losses — and Congressional hearings and a Senate investigation that looked into them — are expected to play a much bigger role this time around.

As a result, JPMorgan has been working behind the scenes to avert losing the vote, calling a wide swath of shareholders to encourage them to cast a ballot. Some big shareholders are scheduled to meet with some directors on the bank’s board so they can air any concerns they might have.

Voting to split the roles would send a powerful message to the bank, but could have serious side effects, something shareholders must weigh. If the vote goes against the company and the board decides to split the role, Mr. Dimon might resign rather than see his powers reduced.

JPMorgan is owned by a wide array of shareholders, from big institutions like the Vanguard Group to mom-and-pop investors. Despite the concerns over the trading loss, the firm’s biggest shareholders, including the asset managers BlackRock and Vanguard, have a history of voting with management, suggesting that it is unlikely the proposal to split the top roles will carry the day.

Nonetheless, firms that advise shareholders on how to vote are expected to recommend again that JPMorgan separate the two top posts. While voting has already begun, most shareholders typically vote in the two weeks leading up to the annual meeting. One big JPMorgan shareholder who has yet to vote and is not authorized to speak on the record said he believed the vote would be close.

“There is so much attention on JPM’s situation that shareholders who might previously have voted to keep the roles together will this year think twice about it because there is bound to be increased scrutiny on how everyone votes,” the shareholder said.

A version of this article appeared in print on 04/30/2013, on page B1 of the NewYork edition with the headline: Another Executive Leaves JPMorgan, Raising Questions as Vote Nears.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/29/another-executive-leaves-jpmorgan-raising-questions-as-vote-nears/?partner=rss&emc=rss