CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

On Monday I wrote an article (the first in a series about work-life balance) profiling a middle-class working mother who persuaded her employer to give her a more flexible schedule. I’ve gotten a lot of questions about why the article focused on mothers and not fathers.

The main reason is that, for this first article, we were interested in exploring the ways that the advice offered by high-profile books and articles aimed at women, like “Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead” and “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” translates to the situations of middle-class women, who have fewer resources and less bargaining power than the high-powered women who have been most vocal about these issues. We were also interested in whether the assumptions underlying the public conversation about the challenges for working mothers — about what women actually want from their careers — held up.

Much of the public conversation has been about the barriers, both internal and external, that women face in getting to leadership positions. But after interviewing dozens of middle-class women and mothers around the country and looking at survey data about women’s desired work arrangements, I found that a lot of mothers were yearning for more flexibility and time at home, not a more direct path up the career ladder. So I decided to shadow a middle-class working mother who had recognized those as her own priorities and who had been proactive about implementing them in her own life.

None of this is to say, of course, that working fathers don’t have their own challenges in juggling work and family responsibilities, especially as gender roles have changed. As I wrote on Monday, men are doing more child care and other household duties than they did in the past, and survey data indicate that men are experiencing more work-family conflict than ever.

A future article about work-family balance, in fact, is likely to focus on the barriers that men face in requesting things like paternity leave and flex time, which may imply to their bosses that they’re not sufficiently “serious” about their careers. (As I have written before, other countries have been more successful in reducing the stigma associated with taking paternity leave.)

Survey data show that there are plenty of men out there who want to work fewer hours than they currently are, after all.

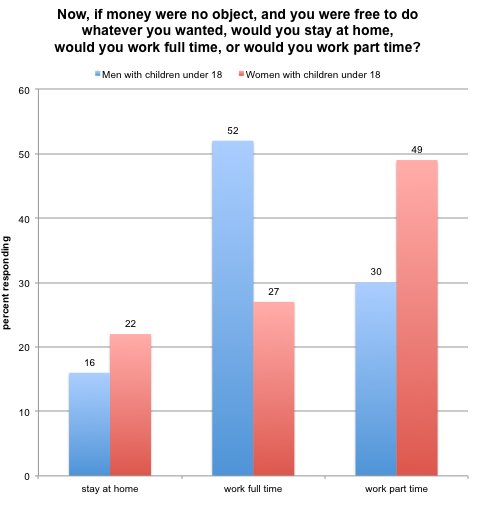

I wrote in Monday’s article that “among all mothers with children under 18, just a quarter say they would choose full-time work if money were no object and they were free to do whatever they wanted, according to a recent New York Times/CBS News poll. By comparison, about half of mothers in the United States are actually working full time, indicating that there are a lot out there logging many more hours than they want to be.” On Twitter and elsewhere, people have asked me what the results were for fathers, so I’ll share here: Just over half of all fathers with children under 18 say their ideal situation would be to work full time, if money were no object. Another 30 percent of these fathers would prefer to work part time, and 16 percent would stay at home.

Results from New York Times/CBS News poll conducted May 31-June 4, 2013.

Results from New York Times/CBS News poll conducted May 31-June 4, 2013.

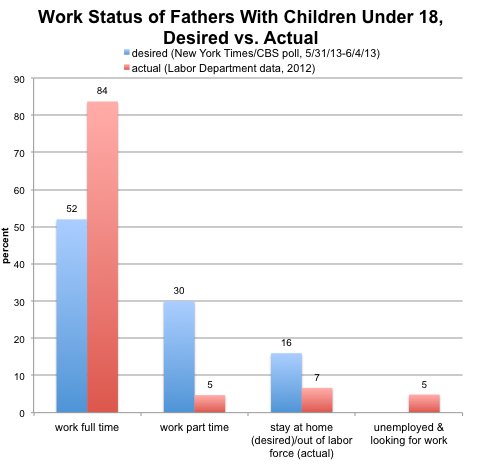

The share of fathers who would ideally work full time is about twice that for mothers. But on the other hand, if you look at the even larger share of fathers who are actually working full time — about 84 percent, according to 2012 Labor Department data — you’ll notice that a lot of fathers are working more hours than they’d like to.

Here’s a look at how these poll results for desired work status line up with the most directly comparable data we have on actual work status, which are for fathers who share a household with their minor children:

Blue bars show results from New York Times/CBS News poll conducted May 31-June 4, 2013, and refer to share of all survey respondents who are fathers of children under 18. Red bars show 2012 Labor Department data, and refer to share of total civilian noninstitutional population of fathers who live with their own children (including stepchildren and adopted children). Unemployed workers could be looking for part-time work or full-time work.

Blue bars show results from New York Times/CBS News poll conducted May 31-June 4, 2013, and refer to share of all survey respondents who are fathers of children under 18. Red bars show 2012 Labor Department data, and refer to share of total civilian noninstitutional population of fathers who live with their own children (including stepchildren and adopted children). Unemployed workers could be looking for part-time work or full-time work.

As you can see nearly a third of surveyed fathers with minor children would like to be working part time, but as of 2012, just 5 percent actually were.

What barriers — financial, cultural, psychological — do you think keep so many fathers from working the shorter hours they say they would ideally like to work?

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/10/working-parents-wanting-fewer-hours/?partner=rss&emc=rss