After decades of college tuition rising faster than inflation or middle-class families’ incomes, something had to give. And now looks like that moment: Expect a debate over how to fix the system of providing and paying for higher education in the 115th Congress and in the administration of the nation’s 45th president.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

To understand that debate, it helps to step back from campaign slogans and look at the underlying economics of higher education — both the ways it has gone wrong and the various philosophical approaches to fixing it.

Start With a Simple Question

What makes education different from any other expensive thing people buy? Why is buying a college education so different from, say, buying a car?

For one, because education is the path to higher-paying work, society has decided that it’s important to help lower-income people attain it. By contrast, there’s not much case for government intervention to make sure people have access to a nice car. Also, when buying a car, it’s a lot easier to predict whether you’re getting a good deal. You can test-drive the car and read consumer reviews and pretty much know what you’re getting. With a college degree, the payoff — a more lucrative career — is distant and uncertain.

Finally, for students who must borrow to afford college, private sector lending doesn’t work as well as it does for other types of purchases. With a car loan, collateral can be repossessed if the borrower doesn’t pay. Students have only that uncertain future. If banks were willing to lend to every student who’s in need, the cost — skyscraping interest rates, loan defaults — would be too great for an economy that relies on an educated work force. So an entire structure of federally subsidized loans was created to try to fix that market failure.

Put all this together and you get a market with some weird flaws. In that sense, higher education is more like health care or housing than autos.

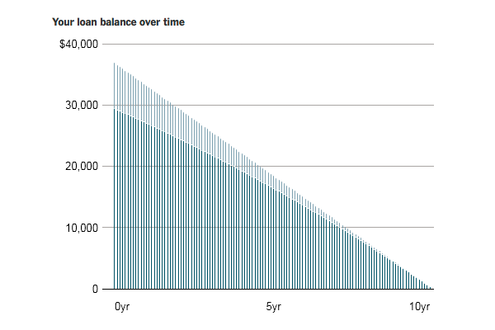

Interactive Graphic

Student Loan Calculator

A guide to student loans at various universities, and what it takes after graduation to repay that debt.

Think of it as a triangle. There is the student who pays tuition for an education. There is the college dispensing the education and collecting that tuition. And then there is the government — state governments, which provide part of the operating budget of public institutions, and the federal government, which provides Pell grants for low-income students and backs loans for students of all income levels.

And once you draw that triangle, the differing approaches of conservative and liberal thinkers to the problem — and the approach that a President Trump or a President Clinton might pursue — become clearer.

The Trump Approach

Mr. Trump hasn’t talked much about higher education and student debt on the campaign trail, at least until Oct. 13, when he unveiled a few details at a rally in Columbus, Ohio, that was billed as his millennial policy speech.

“Students should not be asked to pay more on their loans than they can afford,” he told a crowd bused in from campuses around the state. “The debt,” he said, “should not be an albatross around their necks for the rest of their lives.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

To help young graduates pay off their federal loans, his plan would cap repayment at 12.5 percent of their income and eliminate remaining debt entirely after 15 years. The idea is similar in philosophy to what the Obama administration has done: That program caps debt payments at 10 percent of disposable income and any remaining debt is forgiven after 20 years.

Pundits immediately took to Twitter to frame Mr. Trump’s plan as “left of Obama” and more generous (thus potentially more costly to the government). But the devil — and the politics — is in the details, and the campaign did not respond to requests for an interview.

In Columbus, Mr. Trump also spoke in broad terms about pushing colleges to cut costs more aggressively, particularly by limiting spending on “administrative bloat.”

“There’s not enough incentive for these colleges to cut,” he said. “If the federal government is going to subsidize student loans, it has a right to expect that colleges work hard to control costs and invest their resources in their students.” One incentive: threaten to end their endowments’ tax-free status. He also wants to loosen federal regulations, reducing the cost of compliance “so that colleges can pass on the savings to students,” and he wants universities to tap more of their endowment money.

On one end, then, Mr. Trump intends to tweak the terms of student lending and use federal funds to make debt burdens more manageable; on the other end, he would use the power of the federal government to force colleges and universities to clamp down on tuition increases.

“Trump is essentially trying to deal with the effects of the student loan problem by proposing a new policy somewhat similar to what we have already,” said Mark Huelsman, a senior policy analyst at the liberal think tank Demos. “But his diagnosis of the root causes are misaligned and incorrect.”

The focus on administrative salaries, he said, neglects the bigger problem: the role that the decline in state government support, especially when measured on a spending-per-student basis, plays in the burdens facing college students. Mr. Trump has mentioned no plans to encourage states to spend more to support their public universities.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The Clinton Approach

If Mr. Trump is attacking one linkage in the triangle of students, government and schools, Mrs. Clinton is going after the entire triangle.

Her central pledge is for students from families with an income of under $125,000 a year to be able to attend their state school tuition-free. She wants to do it with a mix of carrots and sticks: new federal resources for tuition grants, for example, but ones that would be available only in states that fund public universities at a high level — an attempt to reverse the drop in per-student state spending over the last decade.

Similarly, Mrs. Clinton’s proposal includes financial penalties for universities that fail to trim costs, reduce tuition and ensure students are able to get good jobs. She wants a contribution from the third corner of the triangle as well, expecting students to work 10 hours a week as part of the debt-free college calculations.

“The problem of rising costs has deep roots,” said Jacob Leibenluft, a senior policy adviser to Mrs. Clinton’s campaign. “We need both new funding and new measures of accountability. Most of all, we need everybody to be part of the solution.”

But every government policy can have unintended consequences. For example, incentives put in place to reward schools that have high graduation rates might, paradoxically, cause schools to refuse admission to lower-income students who are more likely to drop out — and who most need a college education to lift themselves into the middle class.

Beth Akers, a senior fellow at the conservative-leaning Manhattan Institute, raised an additional concern: “We could design a free tuition regime in which the federal government said, ‘We’ll pay your tuition at a public college,’ but then states would have a huge incentive to reduce the money they put into their own institutions.”

To some extent, Mrs. Clinton’s approach echoes the Obama administration’s health care overhaul: In trying to keep existing institutions intact and minimize the financial cost, it ends up being quite complex and creates risks of miscalibration. Incentives for states to increase funding could be too generous, leading to cost overruns, or not generous enough, undermining the goal: to improve the ability of Americans to get an education debt-free.

To conservatives, the proposals amount to excessive confidence in the ability of the federal government to micromanage the sprawling higher education system. “This has kind of been the theme from the left on federal higher education policy, which is: We can make everything better if we just get the formula right,” said Jason D. Delisle, a resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

There’s a similar argument from the left: that a simpler, blunter federal program to reduce college costs, while more expensive for taxpayers, would prove more effective and longer lasting. To carry forward the Obamacare metaphor, it’s the equivalent of arguing that a single-payer health system — one where the government funds all health care — would be better than the current, complex system involving private insurers.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“We’ve had a certain style on the left of doing this sort of policy for a very long time, and I think she’s still kind of caught in the old mode,” said Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of higher education at Temple University and author of “Paying the Price,” a new book about college costs and financial aid. Mrs. Clinton’s approach focuses so much on targeting aid carefully that it could be less effective at reducing costs for everyone.

For a voter deciding between Mr. Trump and Mrs. Clinton based only on how they would approach student debt, the differences are stark. Both set goals of using federal policy to reduce debt burdens for future students, but they adopt different philosophies of government to get there.

Do you think that colleges and universities have become bloated spendthrifts and that the government should deploy a set of threats to force cost cutting? Or do you think that states should shoulder more responsibility, and that greater federal control can encourage them, and their colleges, to fix the problem?

Whatever the outcome, as long as student debt levels keep rising, so will the political pressure around the issue. Whether meaningful legislation results, of course, is a different question.

Continue reading the main story

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/06/education/edlife/presidential-candidates-on-student-debt-in-college.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.