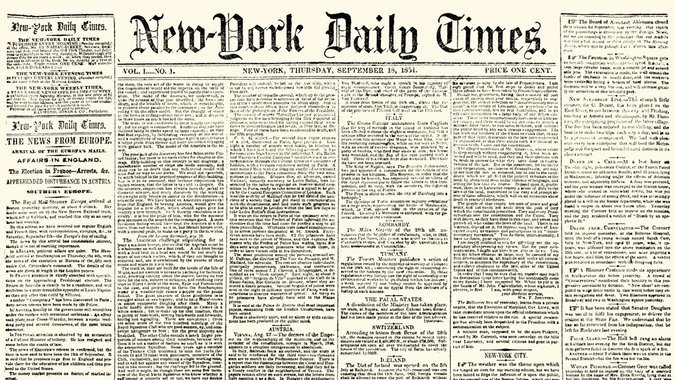

A Maryland slaveholder named Edward Gorsuch had been killed by a group of free and fugitive African-Americans in Christiana as he and a posse, including a federal marshal, tried to capture three young men who had escaped from the Gorsuch farm.

In less than 24 hours, Raymond was in a passion.

“The Christiana Outrage” was the title of his editorial the next day. “Resistance to law is always an offence against the peace of society,” Raymond declared. “A party of whites attempted to arrest several negroes, claiming them as their property, under a law of the United States.”

For Gorsuch did have the law on his side — an abominable, year-old federal law known as the Fugitive Slave Act, which authorized slave owners to “pursue and reclaim” escaped slaves in any state or territory, using “such reasonable force and restraint as may be necessary.”

Citizens — even of free states — were forbidden from helping in an escape, harboring or hiding a fugitive, obstructing a slaveholder’s pursuit or rescuing a recaptured slave from custody.

“No one will contend that these negroes acted from their conscientious convictions of duty,” Raymond wrote. “They acted from passion, from malice, from a determination that the negroes should not perform duties and hold positions which the law had recognized as imposed upon them.”

Contrary to Raymond’s assertion, of course, many Americans did contend that the crowd at Christiana had acted conscientiously and at great peril to themselves as they tried to protect those who sought nothing more or less than their freedom.

Gorsuch, they pointed out, had been warned not to pursue the fugitives. “I’ll have my property or I’ll breakfast in hell,” some accounts had him replying.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But Raymond drew the line at killing. “We have respect for the sincere convictions of an enlightened conscience, even when its dictates do not coincide with our own,” he wrote on Sept. 20 in “The Christiana Affair Again.”

“We can understand perfectly how such convictions may incline others to abstain from all active agency in sending an escaped slave back to his master. But we cannot conceive of any honest or any sane man supposing for one moment that it is his duty to murder his fellows.”

Raymond, obviously, was no abolitionist. Not yet, anyway. He was a politician who served as the speaker of the New York State Assembly and as lieutenant governor of New York. He belonged to the Whig party, which was tearing itself apart in the 1850s trying to accommodate its pro- and antislavery wings.

As their party effectively disintegrated, many northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party. Raymond was prominent among them. In fact, he was chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1864 to 1866.

Yes, a New York Times editor was a distant predecessor of Reince Priebus.

(While I can’t quote our ethics guidelines verbatim, I’m pretty sure the current executive editor would be barred from simultaneously heading a major political party.)

By the time of Raymond’s ascendancy in Republican ranks, abolition had become national policy, with the passage by Congress of the 13th Amendment and its ratification by the states.

On behalf of The Times, Raymond welcomed abolition effusively.

“It perfects the great work of the founders of our Republic,” he wrote in the paper of Feb. 1, 1865.

“With the passage of this amendment the Republic enters upon a new stage of its great career. It is hereafter to be, what it has never been hitherto, thoroughly democratic — resting on human rights as its basis, and aiming at the greatest good and the highest happiness of all its people.”

At last, Raymond’s passion was admirable.

We are constantly reminded by today’s events, however, that it was — to say the least — premature.

Continue reading the main story

Article source: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/18/insider/1851-new-york-times-born-into-racial-turmoil-that-has-never-ended.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.