President Ronald Reagan established a limited pool of imports that it apportioned among foreign producers. The first President George Bush renewed it. Mr. Clinton deployed diplomacy and antidumping measures to protect American steel makers. And in 2002 President George W. Bush put a new ring of “safeguards” around steel that lasted 20 months, until the World Trade Organization ruled them illegal.

They mostly shrugged off the repercussions for the many manufacturing companies that relied on steel. But in 2003, the United States International Trade Commission surveyed manufacturers about the effects. Not only did the tariffs imposed by the Bush administration put many American companies at a competitive disadvantage, but companies also reacted in ways that did the American economy no good.

Almost 500 steel consumers responded to at least some of the questions asked by the commission. About half of respondents reported paying higher prices. And roughly half reported problems procuring steel of the quality and quantity they needed. Over a third reported delayed deliveries; 132 reported steel shortages. About one in six said these problems had reduced sales, and one in three said they had cut into its profitability. A total of 82 companies — including 11 makers of auto parts, nine welded-pipe producers and five makers of fasteners — said they had lost sales to foreign competitors because of the higher cost of steel.

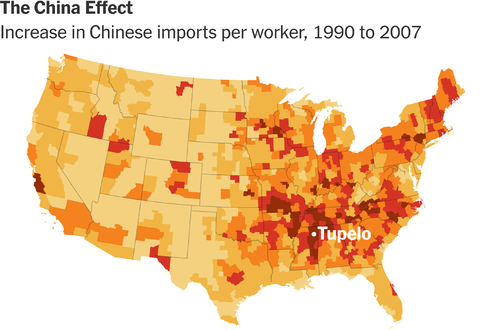

Graphic

How Trump’s Protectionism Could Backfire

President Trump’s tariffs against steel and aluminum imports, designed to protect blue-collar workers, could instead undermine their livelihood.

Some steel consumers shifted from importing steel to importing assembled steel parts that were not subject to the new tariffs. York International — which makes air-conditioning systems, furnaces and the like — reported importing steel assemblies and complete products from overseas. The auto-part maker Metaldyne simply moved some of its operations to South Korea, where it could obtain cheaper steel.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Larsen is sympathetic to the plight of American steel companies. Though it is owned today by Everest Kanto Cylinder based in Mumbai, India, CP Industries emerged as an independent company in a 1989 spinoff from U.S. Steel. And still, whatever old loyalties persist, it makes little sense to force the company to obtain its steel domestically. For starters, no company in the United States produces pipes big enough to make its trademark six-ton containers.

The company estimated that it could get only a fifth of the steel pipe it needed domestically, from only one American firm. Domestic pipe is, moreover, delivered in random lengths and requires additional milling, cutting and testing, raising processing costs by about 16 percent. And Chinese pipes are much cheaper, the company added: Pipes from China delivered in Philadelphia cost $1,680 per metric ton, while U.S. Steel is charging $2,728 per metric ton at its works in Lorain, Ohio. A 25 percent tariff will not close the gap.

CP Industries isn’t simply going to let itself be pushed out of business. An option to consider is importing German steel — which so far has been exempted from the protectionist fusillade. But it will take time to shift suppliers. And German steel will be more expensive.

Of course, there is lobbying. CP Industries has requested a waiver from the tariffs, and it is working to get Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation on its side. Something else it could do is move part or all of the manufacturing process overseas to avoid the steel tariffs.

“We have a whole list of ideas that we could execute,” Mr. Larsen told me. “But nothing we do will be more efficient than what we are doing now. And it will mean less value added in the United States.”

Mr. Larsen is not, by the way, an evangelist for free trade at all costs. Six years ago, when he was at Taylor-Wharton International, a manufacturer of smaller vessels for high-pressure gas, he teamed up with Norris Cylinder to bring an antidumping case against Chinese rivals and won. The government imposed an antidumping duty on Chinese imports to level the playing field.

He would love to try that approach against his new Chinese competitors. But Mr. Trump nipped the strategy in the bud: Dumping — selling below cost in order to drive rivals out of business and gain market share — is not necessary when you are suddenly granted a 10 percent cost advantage. That’s roughly the kind of edge that the steel tariffs gave the makers of high-pressure gas vessels in China.

“As it stands today,” Mr. Larsen lamented, “they cannot be overcome.”

Continue reading the main story

Article source: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/10/business/economy/tariffs-steel.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.