Advertisement

JUNE 13, 2017

By

A new president takes office with big plans, and needs a booming economy to help underwrite his promises. A Federal Reserve chief sees an economy starting to overheat, and begins warning of the need for higher interest rates.

They were bound to clash: Lyndon B. Johnson, the new president, and William McChesney Martin, the longtime, fiscally conservative Fed chairman.

It is a conflict from the 1960s with echoes in the present day, as President Trump’s campaign talk of robust tax cuts, job growth and economic expansion is bumping up against calls by the Fed chairwoman, Janet L. Yellen, for a cautious rise in interest rates, lest inflation get out of control.

Today, when Ms. Yellen acts, we figure she is not doing Mr. Trump’s bidding. She and Fed policy makers are expected this week to increase the benchmark rate for the fourth time in less than two years. But that independence was not always assumed in the Fed’s early years, and Martin’s standoff with Johnson provided a template for interactions between the Federal Reserve and the White House for decades to come.

Advertisement

Within days of ascending to the White House after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, Johnson had an agenda that included passage of a big income tax cut that had been one of Kennedy’s legislative priorities. A year later, after winning the 1964 election, Johnson pursued fighting two wars: one on poverty, and one in Vietnam. Both would lead to significant budget deficits.

Martin saw all this additional spending as a formula for inflation. He also feared he was not getting accurate information from the administration on their spending plans — that some spending on the Vietnam War was not being reported.

Their conflict led to a fiery climax at the Johnson Ranch near Johnson City, Tex., when Martin was unwilling to bend to the president’s will.

1.

The relationship — destined to range from warm to cagey to confrontational — was off to a good start when, eight days after the tragic shooting in Dallas, Johnson telephoned Martin to express gratitude for a note of support.

Johnson: Bill, I just want to thank you for your most thoughtful and generous letter and I appreciate it so much, and I feel quite comfortable and get strength from the knowledge that you’re at that desk.

Martin: Well, that’s very nice of you, Mr. President. I’m just delighted to do anything I can to be of help. You can count on me completely.

Johnson: Well, you just assume that you’re starting out with someone who doesn’t know much about your shop and then you start to tell me what I ought to know about it.

Martin: Well, I certainly will help in every way that I can, Mr. President. I’m sure you know a great deal already, but I’ll help in every way I can.

2.

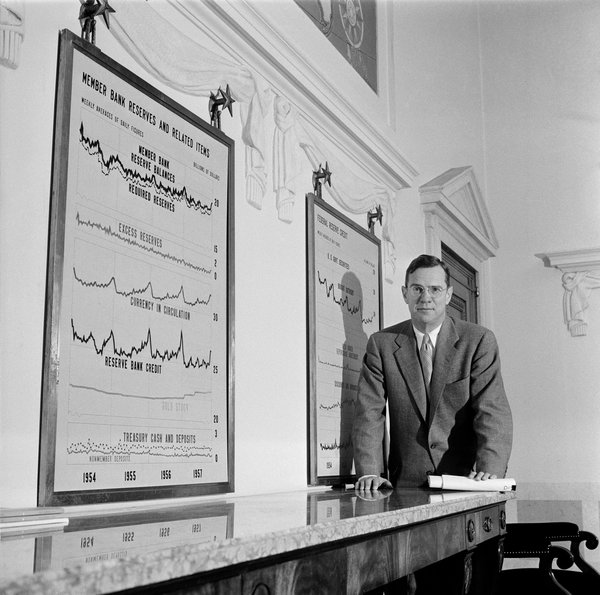

Martin, named the Fed chairman by President Harry S. Truman, was overseeing an economic expansion that had begun two and a half years earlier, in early 1961. But he was keenly aware of the Fed’s role of anticipating and preventing recessions. And he liked a good line. “The function of the Federal Reserve,” he said, “is to take away the punch bowl just as the party is getting good.”

Johnson, the shrewd Texas lawmaker who had seemed out of sorts as Kennedy’s vice president, had no interest in slowing growth. In his first major address after taking office,he called on Congress to pass the income tax cuts first proposed by his predecessor.

“No act of ours could more fittingly continue the work of President Kennedy than the early passage of the tax bill for which he fought all this long year,” he said, speaking to a joint session of Congress and a national television audience. A thunderous ovation followed.

Less than a month later, Martin, caricatured by the political cartoonist Herblock as a tightwad with a stiff, high collar, said the prospect of a tax cut was causing “excessive optimism.”

“If the present euphoria should be translated by a tax cut in a real surge in the economy,” he warned Fed policy makers on Dec. 17, “the system might be faced with the need for a change in the discount rate or some other drastic action to be taken at the first opportunity.”

3.

By March 1964, Congress had passed the tax cut and the economy was cruising. In August, Guy Noyes, the Fed’s chief economist, was nothing short of effusive. “It is hard to be critical of the recent performance of the economy,” he said. “It has been little short of magnificent.”

Advertisement

This rosy picture was disrupted by an event across the Atlantic.

Johnson: Hi, Bill.

Martin: Hello, Mr. President.

Johnson: How’re ya.

Martin: Fine. I thought that, I had a little press conference …

Johnson: Yup.

Martin: … this afternoon on this action we took.

Martin’s folksy banter belied a crisis that had demanded quick reflexes by the Fed. By a narrow margin, British voters elected the first Labour government in 15 years, and its ministers followed with a series of big spending plans to nationalize industries and expand social services. The prospect of inflation prompted currency traders to dump the British pound, forcing the Bank of England to raise its discount rate to 7 percent from 5 percent, a huge jump. To prevent those higher rates from drawing dollars away from the United States, the Fed raised its own rate, by one-half of 1 percentage point.

Martin: What I said to the press was this, that I wanted to make it clear that we would not have raised the discount rate at this time if it had not been for the British action, that we had been for some time watching the possibility of inflationary pressures developing or some problems with the balance of payments developing, but that you had indicated that you wanted us to stimulate the economy in every way that we could. … We have not — the Federal Reserve — given them any advice or had they asked any advice. We had informed them of what we were doing, but we had taken our action entirely independently, and as an insurance premium on behalf of the American dollar.

Johnson: That’s good.

Martin: I just wanted you to know. You know, you never can tell what the press will do with these things.

Johnson. Yup.

Johnson seemed to appreciate how Martin used a news conference to calm any distress in the markets, but he had one question: Would the rate increase tighten the money supply in the United States?

Johnson: You don’t see in this any lack of availability of funds?

Martin: I don’t see any at all. We’re watching it very carefully in the exchange market, and the market behaved pretty well today — of course, this was before our announcement this afternoon. But my guess is that we can handle it and we’re going to try to increase, actually increase over the next 10 days, the availability of money through the reserve mechanism.

Johnson: That’s wonderful, Bill. I hope you’ll watch that and do everything you can. I’d hate for this to turn the other way on us.

4.

In Martin’s eyes the situation was already turning, and in 1965 he began speaking publicly about his concerns. He was afraid the growing cost of the Vietnam War would force a devaluation of the dollar. He saw yet another budget deficit (there had been several in a row) at a time when budget deficits were still looked at askance. In a speech in May, he called it an era of “perpetual deficits and easy money” — red flags among central bankers.

Then in June, at Columbia University, he laid down the gauntlet in a speech that described “disquieting similarities” between the current economic climate and the years leading to the Great Depression: “Then, as now, government officials, scholars and businessmen are convinced that a new economic era has opened, an era in which business fluctuations have become a thing of the past.”

His words were heard. That afternoon the New York Stock Exchange had one of its sharpest declines since Kennedy’s assassination, and the next day The New York Times reported on Page 1 that “Reserve Board Chief Compares Boom Today With That of 20’s.” Johnson, at his next news conference, went out of his way to dispel “gloom and doom” about the economy.

Behind the scenes Johnson was viscerally angry over Martin’s remarks. According to Robert P. Bremner in his book “Chairman of the Fed,” Johnson asked his attorney general, Nicholas Katzenbach, to determine if a president could legally remove a Fed board member from office. (He was advised that disagreeing with administration policies did not constitute “termination for cause.”)

5.

In late November Martin signaled to Johnson’s Treasury secretary that he thought he would have the votes for a rate increase at the Fed’s Dec. 3 meeting. The secretary, Henry H. Fowler, relayed this news to Johnson, and they agreed that Martin should delay any action, at least until January, when the administration’s budget estimates would be available.

Martin’s behavior, Fowler said, was giving Americans the impression there were “two quarterbacks” running the economy — Martin and Johnson.

Fowler: We ought to really try to hold him back now. One, because it’s not the right way to operate — it’s just not right for him to go ahead without knowing what the cards are. Number two, it makes the country feel that we’re divided, and it makes the country feel there are two quarterbacks down here — one fellow’s playing one game and one fellow’s playing another. And as I told him the other day, the country is entitled to have the assurance that its economic and financial policies are being determined by a sensible group of reasonable men sitting around together.

On the morning of Friday, Dec. 3, the day of the Fed’s policy-making meeting, Martin again called Fowler to tell him of the imminent rate increase. Johnson, at his Texas ranch recovering from gallbladder surgery, was livid that his calls for a delay were being ignored. Speaking to Fowler by phone, he made a historical reference going back nearly 150 years: the so-called Bank War when President Andrew Jackson whipped up a populist frenzy against Nicholas Biddle and his Bank of the United States, a predecessor of the Federal Reserve.

Johnson: I would hope that he wouldn’t call his board together and have a Biddle-Jackson fight — I’m prepared to be Jackson if he wants to be Biddle — have a fight like that. Right now I don’t want that in public.

Johnson made sure Fowler passed along his warning.

Johnson: It’s going to hurt my pride, and it’s going to hurt my leadership, and it’s going to hurt the best champion business has got in this country.

His voice rising, he then told Fowler they needed to replace Martin with a “tough guy” to run the central bank.

Advertisement

Johnson: Then, Henry, you all got to think of — around the clock, too, before you get sick — as to where we can get a real articulate, able, tough guy that can take this Federal Reserve place.

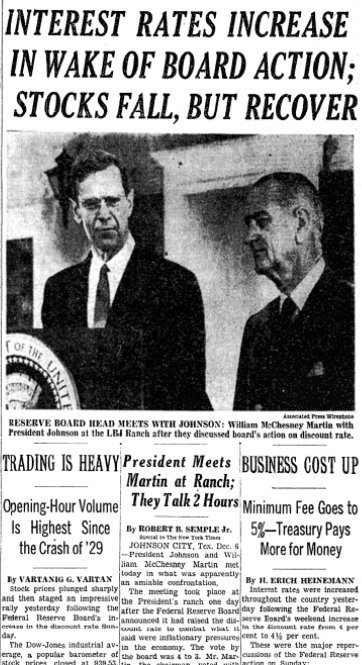

Martin resisted the appeals. At the Board of Governors meeting that afternoon, he called for a vote to raise the discount rate a half-percentage point, to 4.5 percent. But before the vote, he conceded that raising the rate would essentially wave a red flag before the critics of an independent Federal Reserve, in Congress and in the White House. “We should be under no illusions,” he told his colleagues. “A decision to move now can lead to an important revamping of the Federal Reserve System, including its structure and operating methods. This is a real possibility and I have been turning it over in my mind for months.”

The vote was 4 to 3. Martin cast the deciding ballot.

In Texas, Johnson was enraged. Joseph Califano, an aide (later a cabinet secretary under President Jimmy Carter), recalled Johnson’s “burning up the wires to Washington, asking one member of Congress after another, ‘How can I run the country and the government if I have to read on a news-service ticker that Bill Martin is going to run his own economy?’”

Martin was summoned to explain why he had defied the president.

6.

Martin flew down to the Johnson Ranch on Monday, Dec. 6, along with Fowler and other advisers. The president met them at an airstrip behind the wheel of his Lincoln convertible. They piled in and he drove them to the house.

There, Johnson got Martin alone and did not mince words. According to different accounts, the 6-foot-4 Johnson pushed the shorter Martin up against a wall.

“You went ahead and did something that you knew I disapproved of, that can affect my entire term here,” Johnson said, as Martin recalled later in an oral history. “You took advantage of me and I’m not going to forget it, because here I am, a sick man. You’ve got me into a position where you can run a rapier into me and you’ve run it.”

“Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need,” he said.

Martin stood his ground. He pointed out that he had given the president fair warning that a raise was coming. More broadly, he insisted that he and the president had different jobs to do, that the Federal Reserve Act gave the Fed responsibility over interest rates.

“I knew you disapproved of it, but I had to call the shot as I saw it,” he said.

The two eventually stepped outside and tried to assure reporters that any differences had been patched up. Their sour expressions, captured in newspapers the next day, suggested otherwise.

Despite their differences, Johnson renominated Martin to the Fed chairman’s job one year later. Martin would step down in 1970 during the administration of Richard M. Nixon, the fifth president he served under, after having had the longest term of any Fed chief.

The economic expansion that started in 1961 would continue until nearly 1970 —the second longest ever, a credit to Martin’s stewardship. But many argue that he was too slow to raise the discount rate.

In fact, the increase in rates approved in December 1965 did little to control inflation, which would creep higher after the mid-1960s and become a defining issue in the next two decades. A successor, Paul A. Volcker, was forced to push interest rates to nearly 20 percent to bring prices down.

Advertisement

In the end, it appears Martin left the punch bowl out too long.

Sources: “Chairman of the Fed: William McChesney Martin Jr. and the Creation of the American Financial System,” by Robert P. Bremner; and “The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve,” by Peter Conti-Brown

Audio recordings from the LBJ Presidential Library, Austin, Tex.

Article source: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/13/business/economy/a-president-at-war-with-his-fed-chief-5-decades-before-trump.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.