Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesHarshul Sanghi inside American Express’s venture capital office in Facebook’s old headquarters in downtown Palo Alto, Calif.

Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesHarshul Sanghi inside American Express’s venture capital office in Facebook’s old headquarters in downtown Palo Alto, Calif.

MENLO PARK, Calif. — New York, London and Hong Kong are common addresses for blue-chip multinationals. Now Silicon Valley is, too.

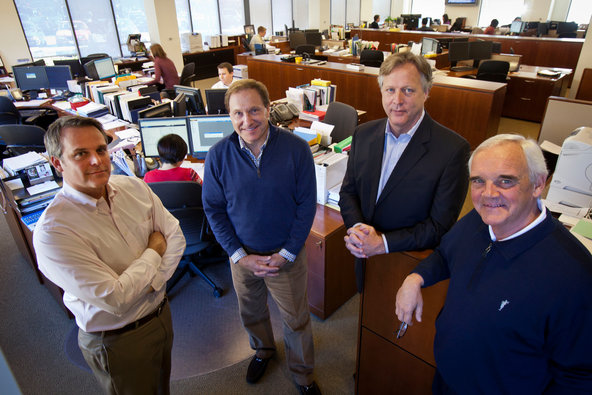

From downtown San Francisco to Palo Alto, companies like American Express and Ford are opening offices and investing millions of dollars in local start-ups. This year, American Express opened a venture capital office in Facebook’s old headquarters in downtown Palo Alto. Less than three miles away, General Motors’ research lab houses full-time investment professionals, recent transplants from Detroit.

“American Express is a 162-year-old company, and this is a moment of transformation,” said Harshul Sanghi, a managing partner at American Express Ventures, the venture capital arm of the financial company. “We’re here to be a part of the fabric of innovation.”

The companies are raising their profiles in Silicon Valley at a shaky time for the broader venture capital industry. While top players like Andreessen Horowitz and Accel Partners have grown bigger, most venture capital firms are struggling with anemic returns.

The market for start-ups has also dimmed, in the wake of the sharp stock declines of Facebook, Zynga and Groupon, the once high-flying threesome that was supposed to lead the next Internet boom.

But unlike traditional venture capitalists, multinationals are less interested in profits. They are here to buy innovation — or at least get a peek at the next wave of emerging technologies.

In August, Starbucks invested $25 million in Square, the mobile payments company based in San Francisco, which will be used in the coffee chain’s stores. This year, Citi Ventures, a unit of Citigroup, invested in Plastic Jungle, an online exchange for gift cards, and Jumio, an online credit card scanner.

Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, the large Spanish banking group, opened an office in San Francisco last year. The team, which has about $100 million to fund local start-ups, is looking for consumer applications that will help the bank create new businesses and better understand its customers.

“We are in one of the most regulated and risk-averse industries in the world, so innovation doesn’t come naturally to us,” said Jay Reinemann, the head of the BBVA office. “We want to avoid the video-rental model. We want to evolve alongside our consumers.”

The companies are hoping to tap into the entrepreneurial mind-set. Multinationals, with their huge payrolls and sprawling operations, are not as nimble as the younger upstarts. While they are rich in resources, big companies tend to be more gun-shy and usually require more time to bring a product to market.

“Companies cannot innovate as fast as start-ups; increasingly they realize they have to look outside,” said Gerald Brady, a managing director at Silicon Valley Bank, who previously led the early-stage venture arm of Siemens. “We think it’s happening a lot more than people recognize or acknowledge.”

Of the 750 corporate venture units, roughly 200 were established in the last two years, according to Global Corporate Venturing, a publication that tracks the market. In the last year, corporations participated in more than $20 billion of start-up investments.

Big business has played the role of venture capitalist before, with limited success. During the waning days of the dot-com boom, financial, media and telecommunications companies sank billions of dollars into start-ups.

The collapse was devastating. Although some managed to make money, far more burned through their cash. In 2002, Accenture, the consulting firm, scrapped its venture capital unit after taking more than $200 million in write-downs. The previous year, Wells Fargo reported $1.6 billion in losses on its venture capital investments. Dell, the computer maker, closed its venture arm in 2004 and sold its portfolio to an investment firm. (It resurrected the unit last year).

Companies say they are taking a different approach this time. Rather than making big bets across the Internet sector, investments are smaller and more selective.

“We invest with the idea that we’re a potential customer for a company,” Jon Lauckner, G.M.’s chief technology officer said. “We’re not looking to make several $5 million investments and make $10 million on each. That would be nice, but it’s not important.”

As they try to find the right start-ups, some are forging tight bonds with local firms. BBVA, for example, is an investor in 500 Startups, a venture firm that specializes in early-stage start-ups and is run by Dave McClure, a former PayPal executive.

Unilever and PepsiCo are limited partners in Physic Ventures, a venture capital firm designed to help corporate investors build commercial partnerships with portfolio companies. Both Unilever and PepsiCo have installed full-time employees in Physic’s downtown San Francisco offices.

American Express has stacked its investment team with technology veterans. Mr. Sanghi, the head of the office, has spent roughly three decades in Silicon Valley and formerly led Motorola Mobility’s venture arm. Through its network of relationships, the office has met with roughly 300 start-ups in the last six months.

The connections have started to pay off. Vinod Khosla, the head of Khosla Ventures and a co-founder of Sun Microsystems, introduced the American Express team to the executives at Ness Computing, a mobile start-up. In August, American Express partnered with Singtel, the Singapore wireless company, to invest $15 million in Ness.

Mr. Sanghi says Ness is a logical investment and a potential partner. The start-up’s application connects users to local businesses through customized search results.

“It’s trying to bring consumers and merchants together in meaningful ways,” he said. “And we’re always trying to find new ways to build value for our merchant and consumer network.”

For start-ups, a big corporate benefactor can bring resources and an established platform to promote and distribute products. Envia Systems, an electric car battery maker, picked General Motors to lead its last financing round because it wanted to have a close relationship with a major automaker, its “absolute end customer,” said Atul Kapadia, Envia’s chief executive.

Although the company received higher offers from other potential corporate investors, Envia wanted G.M.’s advice on how to build the battery so that one day it could be a standard in the company’s electric cars. After the investment, G.M. offered the start-up access to its experts and facilities in Detroit, which Envia is using.

“You want to listen to your end customer because they will help you figure out what specifications you need to get into the final product,” said Mr. Kapadia.

A marriage with corporate investors can be complicated. Besides G.M., Asahi Kasei and Asahi Glass, the Japanese auto-part makers, are also investors in Envia. They both build rival battery products for Japanese car companies.

Mr. Kapadia, who prizes their insights into Japan’s market, says his company is careful about what intellectual property information it shares with its investors. At board meetings, confidential data about Envia’s customers is discussed only at the end, so that conflicted corporate investors can easily excuse themselves.

“In our marriage, there has not been a single ethics concern, because all the expectations were hashed out in the beginning,” Mr. Kapadia said. “But I can see how this could be a land mine.”

For the big corporations, start-up investing is fraught with the same risk as traditional venture investing. Their bets might be modest, but blowups can be embarrassing and can rankle shareholders, who may see venture investing as a distraction from the core business.

OnLive, an online gaming service, offers a recent reminder.

The company was once a darling of corporate investors, with financing from the likes of Time Warner, AutoDesk, HTC and ATT. At one point, it was valued north of $1 billion.

Despite its early promise, the start-up crashed in August, taking many in Silicon Valley by surprise. The company laid off its employees, announced a reorganization and in the process slashed the value of the shares to zero.

“It can be painful when a deal goes sour,” James Mawson, the founder of Global Corporate Venturing, said.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/09/03/multinationals-stake-a-claim-in-venture-capital/?partner=rss&emc=rss